Working with transactions in SQL Server can feel like navigating a maze blindfolded. On paper, nested transactions look simple enough, start one, start another, commit them both, but under the hood, SQL Server plays by a very different set of rules. And that’s exactly where developers get trapped.

In this post, we’re going to look at what really happens when you try to use nested transactions in SQL Server. We’ll walk through a dead-simple demo, expose why @@TRANCOUNT is more illusion than isolation, and see how a single rollback can quietly unravel your entire call chain. If you’ve ever assumed nested transactions can behave the same way as in Oracle for example, this might clarify a few things you didn’t expect !

Practical example

Before diving into the demonstration, let’s set up a simple table in tempdb and illustrate how nested transactions behave in SQL Server.

IF OBJECT_ID('tempdb..##DemoLocks') IS NOT NULL

DROP TABLE ##DemoLocks;

CREATE TABLE ##DemoLocks (id INT IDENTITY, text VARCHAR(50));

BEGIN TRAN MainTran;

BEGIN TRAN InnerTran;

INSERT INTO ##DemoLocks (text) VALUES ('I''m just a speedy insert ! Nothing to worry about');

COMMIT TRAN InnerTran;

WAITFOR DELAY '00:00:10';

ROLLBACK TRAN MainTran;Let’s see how locks behave after committing the nested transaction and entering the WAITFOR phase. If nested transactions provided isolation between each other, no locks should remain since the transaction no longer works on any object. The following query shows all locks associated with my query specifically and the ##Demolocks table we are working on.

SELECT

l.request_session_id AS SPID,

r.blocking_session_id AS BlockingSPID,

resource_associated_entity_id,

DB_NAME(l.resource_database_id) AS DatabaseName,

OBJECT_NAME(p.object_id) AS ObjectName,

l.resource_type AS ResourceType,

l.resource_description AS ResourceDescription,

l.request_mode AS LockMode,

l.request_status AS LockStatus,

t.text AS SQLText

FROM sys.dm_tran_locks l

LEFT JOIN sys.dm_exec_requests r

ON l.request_session_id = r.session_id

LEFT JOIN sys.partitions p

ON l.resource_associated_entity_id = p.hobt_id

OUTER APPLY sys.dm_exec_sql_text(r.sql_handle) t

where t.text like 'IF OBJECT%'

and OBJECT_NAME(p.object_id) = '##DemoLocks'

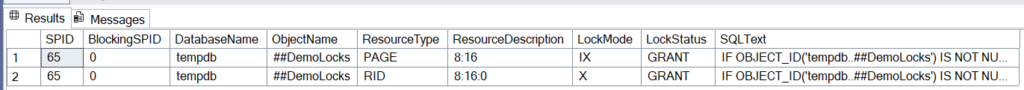

ORDER BY l.request_session_id, l.resource_type;And the result :

All of this was just smoke and mirrors !

We clearly see in the image 2 persistent locks of different types:

- LockMode IX: Intent lock on a data page of the

##DemoLockstable. This indicates that a lock is active on one of its sub-elements to optimize the engine’s lock checks. - LockMode X: Exclusive lock on a

RID(Row Identifier) for data writing (here, ourINSERT).

For more on locks and their usage : sys.dm_tran_locks (Transact-SQL) – SQL Server | Microsoft Learn

In conclusion, SQL Server does not allow nested transactions to maintain isolation from each other, and causes nested transactions to remain dependent on their main transaction, which prevents the release of locks. Therefore, the rollback of MainTran causes the above query to leave the table empty, even with a COMMIT at the nested transaction level. This behavior still respects the ACID properties (Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, and Durability), which are crucial for maintaining data validity and reliability in database management systems.

Now that we have shown that nested transactions have no useful effect on lock management and isolation, let’s see if they have even worse consequences. To do this, let’s create the following code and observe how SQL Server behaves under intensive nested transaction creation. This time, we will add SQL Server’s native @@TRANCOUNT variable, which allows us to analyze the number of open transactions currently in progress.

CREATE PROCEDURE dbo.NestedProc

@level INT

AS

BEGIN

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

PRINT 'Level ' + CAST(@level AS VARCHAR(3)) + ', @@TRANCOUNT = ' + CAST(@@TRANCOUNT AS VARCHAR(3));

IF @level < 100

BEGIN

SET @level += 1

EXEC dbo.NestedProc @level;

END

COMMIT TRANSACTION;

END

GO

EXEC dbo.NestedProc 1;This procedure recursively creates 100 nested transactions, if we manage to go that far… Let’s look at the output.

Level 1, @@TRANCOUNT = 1

[...]

Level 32, @@TRANCOUNT = 32

Msg 217, Level 16, State 1, Procedure dbo.NestedProc, Line 12 [Batch Start Line 15]

Maximum stored procedure, function, trigger, or view nesting level exceeded (limit 32).Indeed, SQL Server imposes various limitations on nested transactions which imply that if they are mismanaged, the application may suddenly suffer a killed query, which can be very dangerous. These limitations are in place to act as safeguards against infinite nesting loops of nested transactions.

Furthermore, we see that @@TRANCOUNT increments with each new BEGIN TRANSACTION, but it does not reflect the true number of active main transactions; i.e., there are 32 transactions ongoing but only 1 can actually release locks.

Ok, but we still didn’t see what a real nested transaction would look like !

I understand, we cannot stop here. I need to go get my old Oracle VM from my garage and fire it up.

Oracle has a pragma called AUTONOMOUS_TRANSACTION that allows creating independent transactions inside a main transaction. Let’s see this in action with a small code snippet.

CREATE TABLE test_autonomous (

id NUMBER PRIMARY KEY,

msg VARCHAR2(100)

);

/

CREATE OR REPLACE PROCEDURE auton_proc IS

PRAGMA AUTONOMOUS_TRANSACTION;

BEGIN

INSERT INTO test_autonomous (id, msg) VALUES (2, 'Autonomous transaction');

COMMIT;

END;

/

CREATE OR REPLACE PROCEDURE main_proc IS

BEGIN

INSERT INTO test_autonomous (id, msg) VALUES (1, 'Main transaction');

auton_proc;

ROLLBACK;

END;

/In this code, we create two procedures:

main_proc, the main procedure, inserts the first row into the table.

auton_proc, called by main_proc, adds a second row to the table.

auton_proc is committed while main_proc is rolled back. Let’s observe the result:

SQL> SELECT * FROM test_auton;

ID MSG

---------- --------------------------------------------------

2 Autonomous transactionNow, that is true isolation between transactions! Here, the inner transaction achieves transactional independence and can persist regardless of the fate of its main transaction. While autonomous transactions in Oracle are not qualified as purely nested because they do not share a common locking context, they serve the same architectural purpose as the one we are demonstrating in this article: allowing a sub-unit of work to decouple its success from the parent flow.

Summary

In summary, SQL Server and Oracle can handle transactions in different ways. In SQL Server, nested transactions do not create real isolation: @@TRANCOUNT may increase, but a single main transaction actually controls locks and the persistence of changes. Internal limits, like the maximum nesting of 32 procedures, show that excessive nested transactions can cause critical errors.

In contrast, Oracle, through PRAGMA AUTONOMOUS_TRANSACTION, allows for truly independent transactions launched from within a main flow. These autonomous transactions can be committed or rolled back without affecting the parent transaction, providing a practical mechanism to decouple specific tasks from the main transactional outcome.

As Brent Ozar points out, SQL Server also has a SAVE TRANSACTION command, which allows you to save a state after a nested transaction has been committed, for example. This command therefore provides more flexibility in managing nested transactions but does not provide complete isolation of sub-transactions. Furthermore, as Brent Ozar emphasizes, this command is complex and requires careful analysis of its behavior and the consequences it entails.

Another approach to bypass SQL Server’s nested-transaction limitations is to manage transaction coordination directly at the application level, where each logical unit of work can be handled independently.

The lesson is clear: appearances can be deceiving! Understanding the actual behavior of transactions in each DBMS is crucial for designing reliable applications and avoiding unpleasant surprises.

![Thumbnail [60x60]](https://www.dbi-services.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/LTO_WEB.jpg)

![Thumbnail [90x90]](https://www.dbi-services.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DWE_web-min-scaled.jpg)

![Thumbnail [90x90]](https://www.dbi-services.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/SIT_web.png)