Introduction

“Make it simple.” This is a principle I keep repeating, and I’ll repeat it again here. Because when it comes to keeping your RAG system’s embeddings fresh, the industry has somehow made it complicated. External orchestrators, custom Python cron jobs, microservices that call microservices, Airflow DAGs with 47 tasks, all to answer a simple question: when my source data changes, how do I update the corresponding embeddings?

If you’ve followed this RAG series from Naive RAG through Hybrid Search, Adaptive RAG, and Agentic RAG, you’ve seen how retrieval quality is the backbone of any RAG system. But here’s what I didn’t cover explicitly: what happens when your retrieval quality silently degrades because your embeddings are stale?

This is the silent killer of RAG in production. Nobody complains about the embedding pipeline, they complain that the chatbot gives wrong answers. And by the time you trace it back to stale embeddings, the trust is already gone.

In this post, I want to bridge two worlds that I’ve been working in simultaneously: the CDC/event-driven pipelines I demonstrated in my PostgreSQL CDC to JDBC Sink and Oracle to PostgreSQL Migration with Flink CDC posts, and the RAG/pgvector world from this series.

The thesis is straightforward: if you’re serious about production RAG, you need event-driven embedding refresh. Batch re-embedding is technical debt waiting to happen. Event-driven architecture and data pipelines are a precondition to hosting similarity search. Organizations that are still 100% batch-processed are all migrating towards event-driven because of a probable need for live KPIs instead of daily refreshes. This is facilitated by the current maturity of the solutions that are out there. The “hidden” bonus of streaming data from your data sources to a data lake and to your data marts is that it facilitates refreshes of embeddings as well.

This is Part 1 covering the architecture and design patterns I feel are relevant. In Part 2, I walk through a hands-on LAB on 25,000 Wikipedia articles with real output, actual numbers, and some of the edge cases you would encounter applying this in practice.

The Problem: Stale Embeddings

Let me paint a picture that I’ve seen in real consulting engagements.

A company builds a RAG system for internal documentation. Knowledge base: 50,000 documents in PostgreSQL. Embeddings generated with text-embedding-3-small, stored in pgvector. Everything works great on day one.

Three months later:

- 2,000 documents have been updated

- 500 new documents have been added

- 300 documents have been deprecated

- The embedding pipeline? It ran once during initial setup. Maybe someone re-ran it manually last month. Maybe not.

The result: your vector index is lying to you. Similarity search returns chunks from outdated documents. The LLM generates answers based on stale context. Users lose trust.

This is not a hypothetical. This is the reality of most RAG deployments I’ve encountered.

Why batch re-embedding doesn’t scale

The naive approach is: “just re-embed everything periodically.” Let’s do the math.

For 50,000 documents, assuming an average of 10 chunks per document:

- 500,000 chunks to embed, ~500 tokens each — that’s 250 million tokens

- At ~$0.02 per 1M tokens with

text-embedding-3-small: ~$5 per full re-embed (not terrible) - The OpenAI embeddings endpoint accepts arrays of inputs, so you can batch ~100 chunks per request. That’s ~5,000 requests. At Tier 1’s 3,000 RPM, RPM isn’t the bottleneck — TPM is. Depending on your tier’s token-per-minute limit (check your project limits), the real constraint is how fast the API will accept 250M tokens. Depending on your usage tier, this could take anywhere from under an hour to several hours of wall-clock time.

- During which, if you’re replacing embeddings in-place (the typical batch approach), your index is in a partially-stale state — some embeddings are new, some are old. The versioned schema I’ll show below avoids this, but most batch implementations don’t bother with versioning.

- In our lab experience, heavy churn from bulk re-inserts can degrade StreamingDiskANN recall (pgvectorscale). The index handles incremental updates well, but re-embedding 500K rows at once is not “incremental” — validate this on your own workload and treat large backfills as an operational event.

Now multiply this by:

- Multiple embedding models you might want to test (remember Part 2 of this series?)

- Multiple environments (dev, staging, production)

- Frequency: weekly? daily? hourly?

The cost isn’t the API calls. The cost is the operational complexity: coordinating the backfill, monitoring progress, handling rate limit errors, and — critically — the lack of observability into which documents actually changed. Batch treats every document the same, whether it was modified yesterday or hasn’t been touched in six months.

The deeper problem: you can’t fix what you don’t measure

But there’s a problem that comes before stale embeddings, and in my consulting experience, it’s far more common: most organizations don’t measure retrieval quality at all. They deploy a RAG system, it works in demo, it goes to production, and then nobody instruments it. There is no precision@k, no nDCG, no confidence scoring. The embedding pipeline might be stale, or it might be fine — they literally cannot tell.

In the Adaptive RAG post, I introduced the metrics framework that makes retrieval quality measurable: precision@k (are the retrieved documents relevant?), recall@k (are we finding all the relevant documents?), nDCG@k (are the best results ranked first?), and confidence scores (how certain is the system about its top result?). In the Agentic RAG post, I added decision metrics on top of that — tracking whether the agent made the right call about when to retrieve. The evaluation framework in the pgvector_RAG_search_lab repository (lab/evaluation/metrics.py, compare_search_configs.py, k_balance_experiment.py) implements all of this concretely.

These metrics were originally designed to compare search strategies and tune parameters. But here’s the connection to embedding freshness that I want to make explicit: the same metrics that tell you whether your search is working also tell you whether your embeddings are drifting. If your weekly nDCG is declining, if your confidence distribution is shifting toward lower values, if precision@10 is dropping for a subset of queries — those are the leading indicators that your embeddings are falling behind your content. Not the queue depth, not the pipeline latency. The quality metrics.

I have seen architectures where teams built elaborate embedding pipelines — cron jobs, Airflow DAGs, custom orchestrators — but never implemented the measurement layer. The pipeline runs on schedule, embeddings get refreshed, and everyone assumes it’s working. But without retrieval quality metrics, you have no way to know if you are going in the right direction. You might be re-embedding documents that don’t need it (wasting API spend) and missing documents that do (degrading search quality). Worse, I have seen setups where the metrics exist but are so poorly instrumented — wrong ground truth sets, no temporal dimension, no per-topic breakdown — that the numbers are misleading. An aggregate nDCG of 0.82 can hide the fact that an entire topic cluster has dropped to 0.45.

Building the pipeline is one thing. Proving you’re going in the right direction is everything.

This is why this post covers both. The first two-thirds address the pipeline: how to detect changes, how to queue and process them, how to decide what’s worth re-embedding. But the final section — Monitoring Embedding Freshness — is where it all comes together. That’s where the retrieval quality metrics from the Adaptive RAG post become operational canaries for embedding drift. The pipeline reacts to content changes; the monitoring layer tells you whether the pipeline is actually keeping your RAG system healthy. You need both.

The Solution: Event-Driven Embedding Refresh

The answer is the same pattern I demonstrated in the CDC posts: react to changes as they happen.

Instead of asking “when should I re-embed?”, the question becomes: “a row changed — which embeddings need updating?”

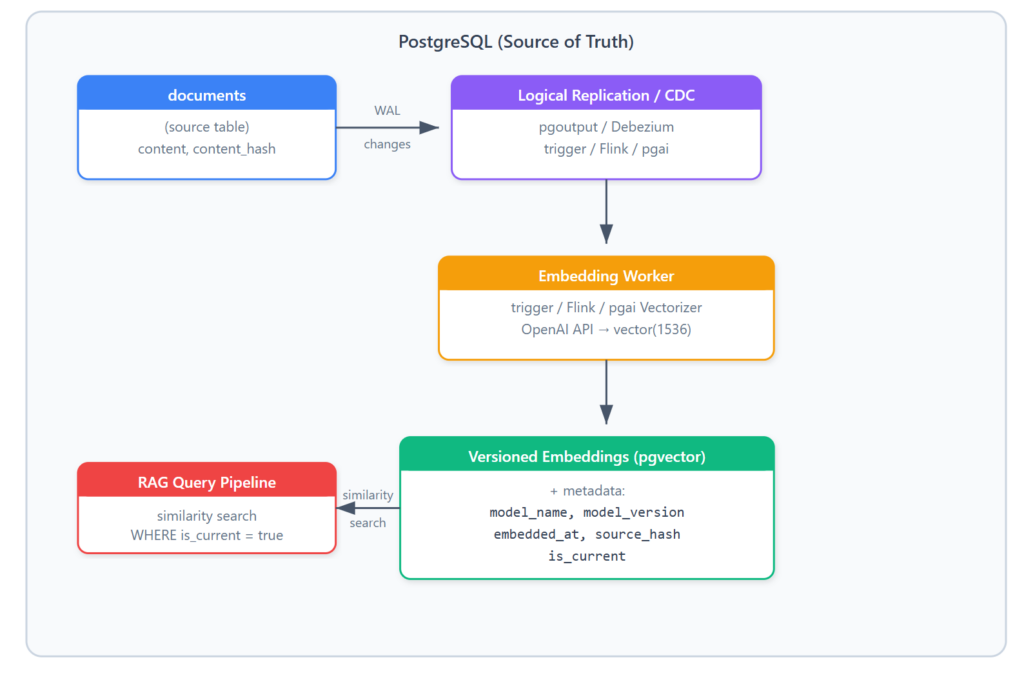

Here’s the architecture I’m proposing:

There are three levels of sophistication here, and I want to walk through each one because not every project needs the most complex solution.

Level 1: PostgreSQL Triggers — The Simplest Path

If your source data and embeddings live in the same PostgreSQL instance (which they probably do if you’ve been following this series), you don’t need Flink. You don’t need Kafka. You need a trigger.

Schema design with versioning

First, let’s design a proper embedding table that supports versioning. This is the piece most tutorials skip:

-- Source table (your knowledge base)

CREATE TABLE documents (

doc_id BIGSERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

title TEXT NOT NULL,

content TEXT NOT NULL,

category TEXT,

content_hash TEXT GENERATED ALWAYS AS (md5(content)) STORED,

updated_at TIMESTAMPTZ NOT NULL DEFAULT now(),

is_active BOOLEAN NOT NULL DEFAULT true

);

-- Embedding table with versioning support

CREATE TABLE document_embeddings (

embedding_id BIGSERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

doc_id BIGINT NOT NULL REFERENCES documents(doc_id) ON DELETE CASCADE,

chunk_index INT NOT NULL,

chunk_text TEXT NOT NULL,

embedding vector(1536), -- text-embedding-3-small

model_name TEXT NOT NULL DEFAULT 'text-embedding-3-small',

model_version TEXT NOT NULL DEFAULT 'v1',

source_hash TEXT NOT NULL, -- md5 of the source content at embed time

embedded_at TIMESTAMPTZ NOT NULL DEFAULT now(),

is_current BOOLEAN NOT NULL DEFAULT true,

UNIQUE(doc_id, chunk_index, model_name, model_version)

);

-- Index for similarity search (only current embeddings)

-- Using pgvectorscale's StreamingDiskANN for better performance at scale

CREATE INDEX idx_embeddings_diskann ON document_embeddings

USING diskann (embedding vector_cosine_ops)

WHERE is_current = true;

-- Index for version lookups

CREATE INDEX idx_embeddings_version ON document_embeddings (doc_id, model_version, is_current);

-- Index for staleness detection

CREATE INDEX idx_embeddings_staleness ON document_embeddings (source_hash, is_current)

WHERE is_current = true;

-- Safety: prevent two "current" chunk sets for the same doc + model space

CREATE UNIQUE INDEX uq_doc_current_per_space

ON document_embeddings (doc_id, model_name, model_version, chunk_index)

WHERE is_current;

A few things to notice here:

content_hash: a generated column that gives us a fast way to detect if content actually changed (not justupdated_at). If you’re adding this to an existing table with data, note thatALTER TABLE ... ADD COLUMN ... GENERATED ALWAYS AS ... STOREDrequires touching/recomputing all rows — plan a maintenance window, or use aBEFORE UPDATEtrigger withNEW.content_hash := md5(NEW.content)instead. Both approaches are functionally equivalent.source_hashon the embedding: captures what the source content looked like when the embedding was generatedis_current: soft versioning — old embeddings are kept for rollback. The partial unique indexuq_doc_current_per_spaceguarantees at the database level that you can never have two “current” chunk sets for the same document within the same model space — even if your application has a bug.- Partial DiskANN index: only indexes current embeddings, so similarity search is clean and performant at scale. Partial indexes (

CREATE INDEX ... WHERE ...) are standard PostgreSQL — validated in our lab with pgvectorscale’s StreamingDiskANN (see Part 2 — Lab Walkthrough). If your pgvectorscale version doesn’t support partial predicates, pgvector’s HNSW partial index is an equivalent fallback. model_version: critical for model upgrades (more on this later)

The embedding queue pattern

Rather than embedding synchronously in a trigger (which would block the transaction and hit external APIs), we use a queue pattern:

-- Queue table for pending embedding work

CREATE TABLE embedding_queue (

queue_id BIGSERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

doc_id BIGINT NOT NULL REFERENCES documents(doc_id),

change_type TEXT NOT NULL DEFAULT 'content_update',

content_hash TEXT,

queued_at TIMESTAMPTZ NOT NULL DEFAULT now(),

claimed_at TIMESTAMPTZ, -- set when a worker claims the item

processed_at TIMESTAMPTZ,

status TEXT NOT NULL DEFAULT 'pending'

CHECK (status IN ('pending', 'processing', 'completed', 'failed', 'skipped')),

error_message TEXT,

retry_count INT NOT NULL DEFAULT 0

);

CREATE INDEX idx_queue_pending ON embedding_queue (status, queued_at)

WHERE status = 'pending';

Note the skipped status — this is used by the change significance detector (covered later) when it determines that a content change is too minor to warrant re-embedding. The item stays in the queue for audit purposes, but no embedding API call is made.

The trigger

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION fn_queue_embedding_update()

RETURNS TRIGGER AS $$

BEGIN

IF TG_OP = 'INSERT' THEN

INSERT INTO embedding_queue (doc_id, change_type, content_hash)

VALUES (NEW.doc_id, 'content_update', NEW.content_hash);

RETURN NEW;

ELSIF TG_OP = 'UPDATE' THEN

-- Only queue if content actually changed (not just metadata)

IF OLD.content_hash IS DISTINCT FROM NEW.content_hash THEN

INSERT INTO embedding_queue (doc_id, change_type, content_hash)

VALUES (NEW.doc_id, 'content_update', NEW.content_hash);

END IF;

RETURN NEW;

ELSIF TG_OP = 'DELETE' THEN

INSERT INTO embedding_queue (doc_id, change_type, content_hash)

VALUES (OLD.doc_id, 'delete', OLD.content_hash);

RETURN OLD;

END IF;

END;

$$ LANGUAGE plpgsql;

CREATE TRIGGER trg_embedding_queue

AFTER INSERT OR UPDATE OR DELETE ON documents

FOR EACH ROW

EXECUTE FUNCTION fn_queue_embedding_update();

The key insight here is the content_hash comparison on UPDATE. If someone updates the category or title but the actual content hasn’t changed, we don’t waste an API call re-embedding identical text. This is a simple optimization but it saves real money at scale. In my lab tests on 25K Wikipedia articles, 12% of simulated mutations were metadata-only — the trigger correctly skipped all of them.

An alternative approach that’s even more targeted: use AFTER INSERT OR UPDATE OF content to only fire the trigger when the content column is modified. This is what I did in the LAB (see Part 2) because the articles table didn’t have a content_hash column originally. Both approaches achieve the same goal.

DBA note on

UPDATE OF: PostgreSQL’s column-specific trigger fires based on theSETlist of theUPDATEcommand, not the actual row diff. If aBEFORE UPDATEtrigger on another function silently modifiesNEW.contentwithoutcontentappearing in the originalSETclause, anAFTER UPDATE OF contenttrigger won’t fire — the content changed, but PostgreSQL doesn’t know. This is documented behavior. Thecontent_hashcomparison approach above doesn’t have this blind spot, because it compares actual values regardless of which columns were in theSETlist.

The worker (Python)

The worker process polls the queue and generates embeddings. This is intentionally simple — no frameworks, no dependencies beyond psycopg and openai:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

"""

embedding_worker.py — polls the embedding_queue and processes pending items.

Run as: python3 embedding_worker.py

python3 embedding_worker.py --once --batch-size 10 (single batch, for testing)

python3 embedding_worker.py --workers 4 (multi-process)

"""

import os, time, hashlib, json

import psycopg

from openai import OpenAI

DB_URL = os.environ["DATABASE_URL"]

client = OpenAI()

MODEL_NAME = "text-embedding-3-small"

MODEL_VERSION = "v1"

CHUNK_SIZE = 500 # tokens (approximate via chars / 4)

CHUNK_OVERLAP = 50

BATCH_SIZE = 10 # queue items per cycle

POLL_INTERVAL = 5 # seconds

def chunk_text(text: str, size: int = CHUNK_SIZE, overlap: int = CHUNK_OVERLAP) -> list[str]:

"""Simple character-based chunking. Replace with your preferred strategy."""

char_size = size * 4 # rough token-to-char ratio

char_overlap = overlap * 4

chunks = []

start = 0

while start < len(text):

end = start + char_size

chunks.append(text[start:end])

start = end - char_overlap

return chunks

def generate_embeddings(texts: list[str]) -> list[list[float]]:

"""Batch embedding call to OpenAI."""

response = client.embeddings.create(

input=texts,

model=MODEL_NAME

)

return [item.embedding for item in response.data]

def process_insert_or_update(conn, doc_id: str, content_hash: str):

"""Generate fresh embeddings for a document."""

with conn.cursor() as cur:

# Fetch current document content

cur.execute(

"SELECT content FROM documents WHERE doc_id = %s AND is_active = true",

(doc_id,)

)

row = cur.fetchone()

if not row:

return # document was deleted or deactivated since queuing

content = row[0]

# Verify content hasn't changed again since queuing

current_hash = hashlib.md5(content.encode()).hexdigest()

if current_hash != content_hash:

return # content changed again, a newer queue entry will handle it

# Check if embeddings already exist for this hash (idempotency)

# Scoped to model_name + model_version so parallel shadow-mode workers

# don't falsely consider each other's embeddings as "already done"

cur.execute(

"""SELECT 1 FROM document_embeddings

WHERE doc_id = %s AND source_hash = %s

AND model_name = %s AND model_version = %s

AND is_current = true

LIMIT 1""",

(doc_id, content_hash, MODEL_NAME, MODEL_VERSION)

)

if cur.fetchone():

return # already embedded with this content

# Chunk and embed

chunks = chunk_text(content)

embeddings = generate_embeddings(chunks)

# Mark old embeddings as not current — scoped to this model space only

# so shadow-mode v2 embeddings aren't flipped by v1 workers (or vice versa)

cur.execute(

"""UPDATE document_embeddings

SET is_current = false

WHERE doc_id = %s

AND model_name = %s AND model_version = %s

AND is_current = true""",

(doc_id, MODEL_NAME, MODEL_VERSION)

)

# Insert new embeddings

for idx, (chunk, emb) in enumerate(zip(chunks, embeddings)):

cur.execute(

"""INSERT INTO document_embeddings

(doc_id, chunk_index, chunk_text, embedding,

model_name, model_version, source_hash)

VALUES (%s, %s, %s, %s, %s, %s, %s)""",

(doc_id, idx, chunk, emb, MODEL_NAME, MODEL_VERSION, content_hash)

)

conn.commit()

def process_delete(conn, doc_id: str):

"""Mark embeddings as not current when source is deleted."""

with conn.cursor() as cur:

cur.execute(

"""UPDATE document_embeddings

SET is_current = false

WHERE doc_id = %s

AND model_name = %s AND model_version = %s

AND is_current = true""",

(doc_id, MODEL_NAME, MODEL_VERSION)

)

conn.commit()

def poll_and_process():

"""Main loop: claim a batch, process, repeat."""

with psycopg.connect(DB_URL) as conn:

while True:

with conn.cursor() as cur:

# Claim a batch (SELECT FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED)

cur.execute("""

UPDATE embedding_queue

SET status = 'processing', claimed_at = now()

WHERE queue_id IN (

SELECT queue_id FROM embedding_queue

WHERE status = 'pending'

ORDER BY queued_at

LIMIT %s

FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED

)

RETURNING queue_id, doc_id, change_type, content_hash

""", (BATCH_SIZE,))

batch = cur.fetchall()

conn.commit()

if not batch:

time.sleep(POLL_INTERVAL)

continue

for queue_id, doc_id, change_type, content_hash in batch:

try:

if change_type in ('content_update',):

process_insert_or_update(conn, doc_id, content_hash)

elif change_type == 'delete':

process_delete(conn, doc_id)

with conn.cursor() as cur:

cur.execute(

"""UPDATE embedding_queue

SET status = 'completed', processed_at = now()

WHERE queue_id = %s""",

(queue_id,)

)

conn.commit()

except Exception as e:

conn.rollback()

with conn.cursor() as cur:

cur.execute(

"""UPDATE embedding_queue

SET status = CASE WHEN retry_count >= 3 THEN 'failed' ELSE 'pending' END,

retry_count = retry_count + 1,

error_message = %s

WHERE queue_id = %s""",

(str(e), queue_id)

)

conn.commit()

print(f"Error processing queue_id={queue_id}: {e}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

print("Embedding worker started. Polling...")

poll_and_process()

What I like about this pattern:

- It’s transactional: the trigger and the queue insert are in the same transaction. If the INSERT/UPDATE fails, no queue entry is created.

- It’s idempotent: the worker checks

content_hashbefore embedding, so duplicate queue entries are harmless. - It uses

SELECT FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKEDfor safe concurrency (see below). - It handles retries gracefully: failed items go back to pending with a counter.

Deep dive: SELECT FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED

This is the core of why this queue pattern works, and it’s a PostgreSQL feature that most people underuse. Let me explain it properly because it’s one of those things that looks simple in the SQL but has profound implications for how you scale workers.

The problem: you want to run multiple embedding workers in parallel to process the queue faster. But if two workers pick the same queue item, you’ve wasted an API call (double embedding) or worse, you get race conditions on the document_embeddings table.

The classic solutions are:

- External locking (Redis, ZooKeeper): adds infrastructure, adds failure modes

- Application-level partitioning (worker 1 handles doc_id % 3 = 0, worker 2 handles doc_id % 3 = 1…): rigid, doesn’t adapt to load

- SELECT FOR UPDATE: locks the rows, but the second worker blocks and waits until the first one commits. This serializes your workers — you’re back to single-threaded throughput.

SKIP LOCKED changes everything. Here’s what happens step by step:

Timeline:

─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Worker A (t=0):

BEGIN;

UPDATE embedding_queue SET status = 'processing', claimed_at = now()

WHERE queue_id IN (

SELECT queue_id FROM embedding_queue

WHERE status = 'pending'

ORDER BY queued_at

LIMIT 5

FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED -- ← locks rows 1,2,3,4,5

)

RETURNING queue_id, doc_id, change_type, content_hash;

→ Returns: queue_id 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

→ These 5 rows are now locked by Worker A's transaction

Worker B (t=1, while Worker A is still processing):

BEGIN;

UPDATE embedding_queue SET status = 'processing', claimed_at = now()

WHERE queue_id IN (

SELECT queue_id FROM embedding_queue

WHERE status = 'pending'

ORDER BY queued_at

LIMIT 5

FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED -- ← sees rows 1-5 are locked, SKIPS them

)

RETURNING queue_id, doc_id, change_type, content_hash;

→ Returns: queue_id 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

→ No blocking, no waiting, no conflict

Worker C (t=2):

→ Gets queue_id 11, 12, 13, 14, 15

→ Same story: zero contention

The key behaviors:

FOR UPDATE: tells PostgreSQL “I intend to modify these rows, lock them for me”SKIP LOCKED: tells PostgreSQL “if a row is already locked by someone else, don’t wait — just pretend it doesn’t exist and move to the next one”

This means:

- Workers never block each other — no waiting, no deadlocks

- Workers never process the same item — each item is claimed by exactly one worker

- You can scale horizontally just by starting more worker processes

- If a worker crashes mid-processing, its transaction is rolled back, the locks are released, and the rows become visible to other workers again (the

statuswas already set to'processing'via the UPDATE, so you’d need a cleanup mechanism for crashed workers — more on that below)

What happens without SKIP LOCKED?

Let’s compare. With plain FOR UPDATE (no SKIP LOCKED):

Worker A (t=0): SELECT ... FOR UPDATE LIMIT 5; → gets rows 1-5, locks them

Worker B (t=1): SELECT ... FOR UPDATE LIMIT 5; → tries row 1... BLOCKED ⏳

waits for Worker A to COMMIT

Worker A (t=10): COMMIT; → releases locks

Worker B (t=10): → finally gets rows 1-5 (but they're already processed!)

→ returns empty set because status is no longer 'pending'

→ wasted 10 seconds waiting for nothing

With SKIP LOCKED:

Worker A (t=0): SELECT ... FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED LIMIT 5; → gets rows 1-5

Worker B (t=1): SELECT ... FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED LIMIT 5; → gets rows 6-10 instantly

→ zero wait time, immediate useful work

This is exactly the behavior you want for a work queue.

The crash recovery problem

There’s one subtlety: if Worker A claims rows 1-5, sets their status = 'processing', and then crashes (process killed, OOM, network failure), those rows are stuck in 'processing' forever. The PostgreSQL locks are released (transaction was rolled back), but the status column still says 'processing'.

You need a reaper — a periodic cleanup that reclaims stale items:

-- Reclaim items stuck in 'processing' for more than 5 minutes

-- (embedding should never take that long)

-- Uses claimed_at, not queued_at — an item queued 30 minutes ago

-- but claimed 10 seconds ago should NOT be reclaimed

UPDATE embedding_queue

SET status = 'pending',

retry_count = retry_count + 1,

error_message = 'reclaimed: worker timeout after 5 minutes'

WHERE status = 'processing'

AND claimed_at < now() - INTERVAL '5 minutes';

Run this every minute via pg_cron or a simple cron job. It’s a safety net, not the primary flow.

Why this is better than external queue systems

For this specific use case (embedding queue), SKIP LOCKED gives you an in-database work queue with:

- ACID guarantees: the queue and the embeddings are in the same database, same transaction scope

- No external dependencies: no Redis, no RabbitMQ, no SQS

- Exactly-once semantics: combined with the

content_hashidempotency check - Observability: it’s just a table —

SELECT count(*) FROM embedding_queue WHERE status = 'pending'is your queue depth, queryable from any SQL client or monitoring tool

The limitation is throughput: if you’re processing millions of queue items per second, you want Kafka or SQS. For an embedding queue where each item takes 100-500ms to process (API call), PostgreSQL can easily handle thousands of items per minute. That’s more than enough for any knowledge base I’ve seen in production.

What I don’t like:

- It’s polling-based: the worker checks every 5 seconds. For most use cases this is fine, but if you need sub-second latency, you want

LISTEN/NOTIFY. - It requires a separate process to run. In production, that means a systemd service or a Kubernetes deployment.

Upgrading to LISTEN/NOTIFY

If you want to eliminate polling and react instantly, PostgreSQL’s LISTEN/NOTIFY mechanism is your friend. Add this to the trigger:

-- Add to fn_queue_embedding_update(), after each INSERT INTO embedding_queue:

-- Use NEW.doc_id for INSERT/UPDATE, OLD.doc_id for DELETE

PERFORM pg_notify('embedding_work', json_build_object(

'doc_id', COALESCE(NEW.doc_id, OLD.doc_id),

'operation', TG_OP

)::text);

And in the worker, replace the time.sleep() loop with:

import select

conn = psycopg.connect(DB_URL, autocommit=True)

conn.execute("LISTEN embedding_work")

while True:

if select.select([conn], [], [], 5.0) == ([], [], []):

# Timeout — check for any missed items anyway

process_pending_batch(conn)

else:

conn.execute("SELECT 1") # consume notifications

for notify in conn.notifies():

process_pending_batch(conn)

This gives you near-real-time embedding refresh with zero polling overhead.

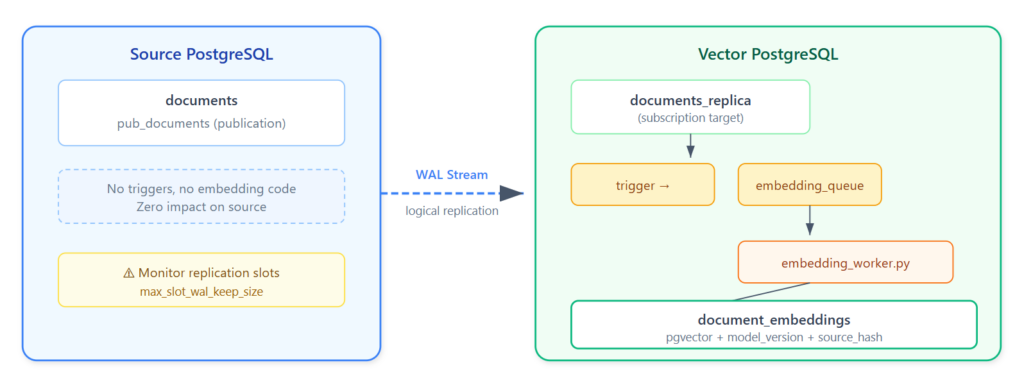

Level 2: Logical Replication — Cross-Database Embedding Sync

Now let’s go a level up. What if your source data lives in a different PostgreSQL instance than your vector store? Or what if the team that manages the knowledge base doesn’t want triggers on their production tables?

This is where PostgreSQL logical replication becomes the CDC mechanism. It’s built into PostgreSQL, it reads the WAL, and it has near-zero impact on the source.

The setup

On the source (knowledge base database):

-- Ensure WAL is configured for logical replication

ALTER SYSTEM SET wal_level = 'logical';

ALTER SYSTEM SET max_replication_slots = 10;

ALTER SYSTEM SET max_wal_senders = 10;

-- Restart required

-- Create a publication for the documents table

CREATE PUBLICATION pub_documents FOR TABLE documents;

On the target (vector database, different instance):

-- Create the same documents table structure (or a subset)

CREATE TABLE documents_replica (

doc_id BIGINT PRIMARY KEY,

title TEXT NOT NULL,

content TEXT NOT NULL,

content_hash TEXT,

updated_at TIMESTAMPTZ,

is_active BOOLEAN

);

-- Create the subscription

CREATE SUBSCRIPTION sub_documents

CONNECTION 'host=source-db port=5432 dbname=knowledge_base user=replicator password=...'

PUBLICATION pub_documents

WITH (copy_data = true); -- initial snapshot

Now the documents_replica table on your vector database is automatically kept in sync via WAL streaming. Every INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE on the source is replicated in near-real-time.

From here, you add the same trigger + queue + worker pattern from Level 1, but on the documents_replica table. The source database team doesn’t need to know or care about your embedding pipeline.

Architecture

Why this is powerful:

- Zero impact on source: no triggers, no extra connections, just WAL reading

- Separation of concerns: the DBA managing the knowledge base doesn’t need to understand embeddings

- Built-in catch-up: if the embedding worker goes down, logical replication buffers changes in the WAL. When it comes back, all changes are processed in order

- No external dependencies: this is pure PostgreSQL, no Kafka, no Flink, no cloud services

Limitations:

- Logical replication is PG → PG only (unlike Flink CDC which can source from Oracle, MySQL, etc.)

- DDL is not replicated: if the source adds a column, you need to handle it manually

- The replication slot retains WAL until consumed — ⚠️ Production pitfall: if the subscriber is down for too long, WAL can fill up the source disk. Set

max_slot_wal_keep_size(PG 13+) to cap retention, and monitorpg_replication_slotsfor inactive slots. DBAs: this is the #1 risk with logical replication.

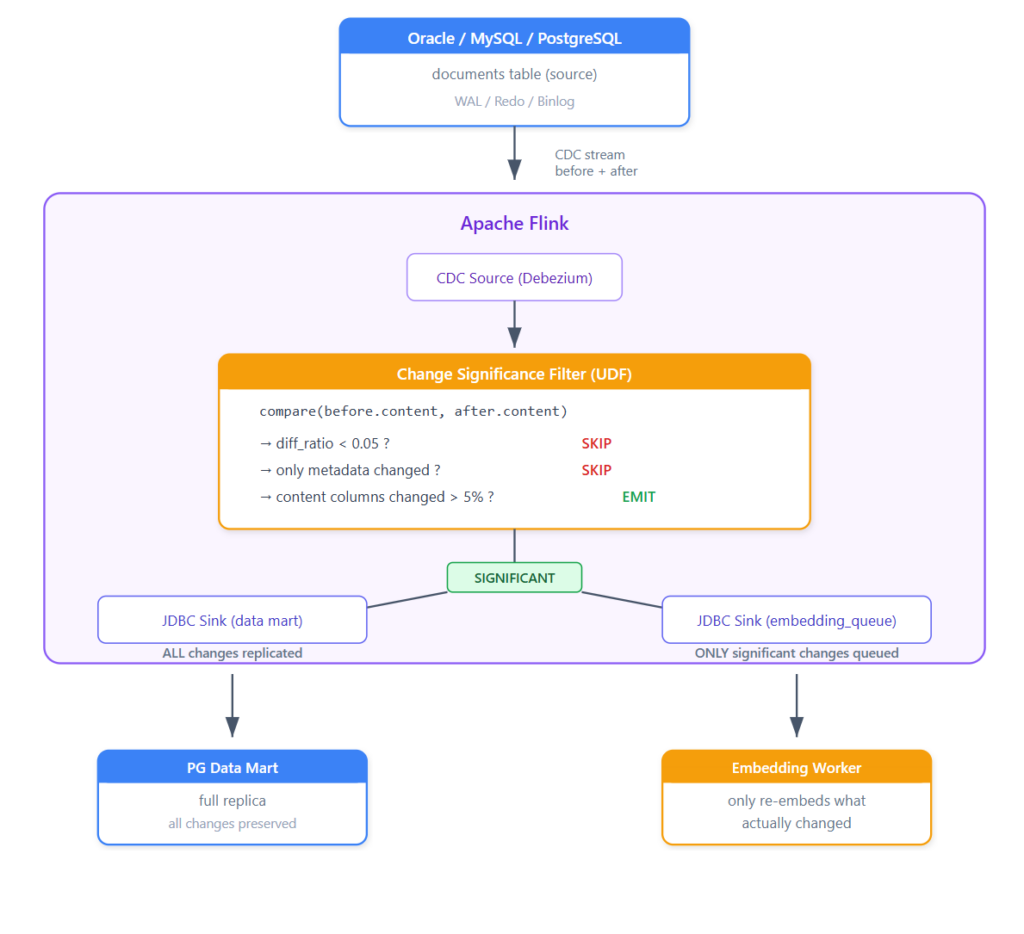

Level 3: Flink CDC — When the Source Isn’t PostgreSQL (and When to Skip Re-embedding)

If your knowledge base lives in Oracle, MySQL, or you need to fan out to multiple targets (pgvector + Elasticsearch + data lake), then we’re back in the territory of my CDC posts.

But here’s where it gets really interesting. Flink CDC gives us something that the trigger and logical replication approaches don’t: access to both the before and after images of every row change. Debezium, which Flink CDC uses under the hood, captures the full row state before and after the UPDATE. This means we can evaluate whether a change is significant enough to warrant re-embedding — directly inside the pipeline, before hitting any embedding API.

Why this matters

Not every UPDATE to a document requires a new embedding. Think about it:

- Someone fixes a typo: “PostgreSLQ” → “PostgreSQL” — probably not worth re-embedding

- Someone updates a metadata field (status, last_reviewed_by) — definitely not worth re-embedding (metadata filtering should be done in the WHERE claude)

- Someone rewrites two paragraphs and adds a new section — yes, re-embed

- Someone changes a single KPI number in a financial report — depends on context, but the semantic meaning shifted

In a busy knowledge base, most row-level changes are minor. If your pipeline blindly re-embeds on every UPDATE, you’re burning API credits, creating unnecessary load on the embedding worker, and churning your DiskANN index for no semantic gain. The question is: can we be smarter about this?

The architecture with change significance filtering

The key insight: separate the data replication (all changes) from the embedding trigger (only significant changes). The data mart gets everything — it’s a faithful replica. But the embedding queue only receives changes where the content actually shifted enough to matter semantically.

Change significance: the approaches

There are several ways to evaluate whether a change is “significant enough” for re-embedding. I want to walk through each one because they have very different trade-offs.

Approach 1: Column-aware filtering (simplest, start here)

The cheapest filter: only trigger re-embedding when specific content columns change. If someone updates status, last_reviewed_by, category, or any metadata field, skip the embedding entirely.

In Flink SQL, Debezium CDC exposes op (operation type) and you can access both the old and new values. Here’s how to implement it:

-- CDC source table with before/after access

CREATE TABLE src_documents (

doc_id BIGINT,

title STRING,

content STRING,

category STRING,

status STRING,

updated_at TIMESTAMP(3),

PRIMARY KEY (doc_id) NOT ENFORCED

) WITH (

'connector' = 'postgres-cdc',

'hostname' = '172.19.0.4',

'port' = '5432',

'username' = 'postgres',

'password' = '...',

'database-name' = 'knowledge_base',

'schema-name' = 'public',

'table-name' = 'documents',

'slot.name' = 'flink_documents_slot',

'decoding.plugin.name' = 'pgoutput',

'scan.incremental.snapshot.enabled' = 'true'

);

-- JDBC sink for ALL changes (data mart replication)

CREATE TABLE dm_documents (

doc_id BIGINT,

title STRING,

content STRING,

category STRING,

status STRING,

updated_at TIMESTAMP(3),

PRIMARY KEY (doc_id) NOT ENFORCED

) WITH (

'connector' = 'jdbc',

'url' = 'jdbc:postgresql://172.20.0.4:5432/vector_db',

'table-name' = 'documents_replica',

'username' = 'postgres',

'password' = '...',

'driver' = 'org.postgresql.Driver'

);

-- Replicate everything to the data mart

INSERT INTO dm_documents SELECT * FROM src_documents;

For the embedding queue, we need to be selective. This is where a Flink SQL view or a ProcessFunction comes in. Since Flink SQL CDC doesn’t natively expose the before-image in the SELECT, the simplest approach is to use the content_hash strategy from Level 1: the trigger on documents_replica compares content_hash and only queues when it actually changed.

But if you want the filtering to happen inside Flink (before hitting the target at all), you need a UDF.

Approach 2: Text diff ratio (UDF — the sweet spot)

This is where it gets interesting. We register a custom Flink UDF that computes the similarity ratio between the old and new content, and only emits the row to the embedding queue when the change exceeds a threshold.

/**

* Flink UDF: computes text change ratio between two strings.

* Returns a value between 0.0 (completely different) and 1.0 (identical).

*

* Uses a simplified approach: character-level diff ratio.

* For production, consider token-level or sentence-level comparison.

*/

@FunctionHint(output = @DataTypeHint("DOUBLE"))

public class TextChangeRatio extends ScalarFunction {

public Double eval(String before, String after) {

if (before == null || after == null) return 0.0;

if (before.equals(after)) return 1.0;

// Longest Common Subsequence ratio

int lcs = lcsLength(before, after);

int maxLen = Math.max(before.length(), after.length());

return maxLen == 0 ? 1.0 : (double) lcs / maxLen;

}

private int lcsLength(String a, String b) {

// Optimized for streaming: use rolling array, not full matrix

int[] prev = new int[b.length() + 1];

int[] curr = new int[b.length() + 1];

for (int i = 1; i <= a.length(); i++) {

for (int j = 1; j <= b.length(); j++) {

if (a.charAt(i-1) == b.charAt(j-1)) {

curr[j] = prev[j-1] + 1;

} else {

curr[j] = Math.max(prev[j], curr[j-1]);

}

}

int[] tmp = prev; prev = curr; curr = tmp;

java.util.Arrays.fill(curr, 0);

}

return prev[b.length()];

}

}

Register and use it in Flink SQL:

-- Register the UDF

CREATE FUNCTION text_change_ratio AS 'com.example.TextChangeRatio';

Now, the challenge here is that Flink SQL CDC doesn’t directly expose the “before” image as a column you can SELECT. The changelog stream has INSERT (+I), UPDATE_BEFORE (-U), UPDATE_AFTER (+U), and DELETE (-D) operations, but in a standard SELECT * FROM cdc_table, you only see the latest state.

To access both before and after, you have two options:

Option A: Stateful ProcessFunction (Java/Python)

This is the cleanest approach. You write a KeyedProcessFunction that maintains the previous state of each document in Flink’s managed state, and compares it with the incoming change:

# Pseudocode for the ProcessFunction approach

class ChangeSignificanceFilter(KeyedProcessFunction):

def __init__(self, threshold=0.95):

self.threshold = threshold # 0.95 = skip if 95%+ similar

def open(self, runtime_context):

# Flink managed state: stores last known content per doc_id

self.last_content = runtime_context.get_state(

ValueStateDescriptor("last_content", Types.STRING())

)

def process_element(self, row, ctx):

doc_id = row['doc_id']

new_content = row['content']

old_content = self.last_content.value()

# Always update state

self.last_content.update(new_content)

if old_content is None:

# INSERT: always emit (new document)

yield Row(doc_id=doc_id, needs_embedding=True,

change_ratio=0.0, operation='INSERT')

return

if old_content == new_content:

# Content identical: metadata-only change, skip

return

# Compute change ratio

ratio = text_similarity(old_content, new_content)

if ratio < self.threshold:

# Significant change: emit for re-embedding

yield Row(doc_id=doc_id, needs_embedding=True,

change_ratio=round(1.0 - ratio, 4),

operation='UPDATE')

else:

# Minor change (typo fix, formatting): skip embedding

# Optionally log for monitoring

yield Row(doc_id=doc_id, needs_embedding=False,

change_ratio=round(1.0 - ratio, 4),

operation='SKIP')

def text_similarity(a: str, b: str) -> float:

"""Fast similarity using difflib SequenceMatcher."""

from difflib import SequenceMatcher

return SequenceMatcher(None, a, b).ratio()

Option B: Self-join with temporal table (Flink SQL)

If you want to stay in pure SQL, you can maintain a “previous version” table and join against it:

-- Maintain a snapshot of previous content in a JDBC-backed table

CREATE TABLE content_snapshots (

doc_id BIGINT,

content STRING,

content_md5 STRING,

PRIMARY KEY (doc_id) NOT ENFORCED

) WITH (

'connector' = 'jdbc',

'url' = 'jdbc:postgresql://172.20.0.4:5432/vector_db',

'table-name' = 'content_snapshots',

'username' = 'postgres',

'password' = '...',

'driver' = 'org.postgresql.Driver'

);

-- Write ALL changes to the snapshot table (upsert)

INSERT INTO content_snapshots

SELECT doc_id, content, MD5(content) FROM src_documents;

Then in the embedding trigger on the target side, compare the incoming content_md5 against the previously stored one. If they differ, queue for embedding. This is essentially what the Level 1 trigger does, but now the CDC pipeline is handling the cross-database transport.

Approach 3: Structural change analysis (most sophisticated)

For knowledge bases with structured content (Markdown, HTML, technical documentation), you can go deeper than raw text diff. Analyze what kind of change happened:

def analyze_change_significance(old_content: str, new_content: str) -> dict:

"""

Analyze the structural significance of a content change.

Returns a dict with metrics to decide whether re-embedding is needed.

"""

import re

from difflib import SequenceMatcher

result = {

'char_ratio': SequenceMatcher(None, old_content, new_content).ratio(),

'paragraphs_added': 0,

'paragraphs_removed': 0,

'paragraphs_modified': 0,

'heading_changed': False,

'needs_embedding': False

}

# Split into paragraphs

old_paras = [p.strip() for p in old_content.split('\n\n') if p.strip()]

new_paras = [p.strip() for p in new_content.split('\n\n') if p.strip()]

old_set = set(old_paras)

new_set = set(new_paras)

result['paragraphs_added'] = len(new_set - old_set)

result['paragraphs_removed'] = len(old_set - new_set)

# Check if headings changed (strong signal for semantic shift)

old_headings = set(re.findall(r'^#{1,3}\s+(.+)$', old_content, re.MULTILINE))

new_headings = set(re.findall(r'^#{1,3}\s+(.+)$', new_content, re.MULTILINE))

result['heading_changed'] = old_headings != new_headings

# Decision logic

if result['heading_changed']:

result['needs_embedding'] = True

result['reason'] = 'heading_changed'

elif result['paragraphs_added'] > 0 or result['paragraphs_removed'] > 0:

result['needs_embedding'] = True

result['reason'] = 'structural_change'

elif result['char_ratio'] < 0.90:

result['needs_embedding'] = True

result['reason'] = 'significant_text_change'

else:

result['needs_embedding'] = False

result['reason'] = 'minor_change'

return result

The idea here is that structural changes (new headings, added/removed sections) almost always shift the semantic meaning enough to warrant re-embedding, while inline text modifications need to cross a threshold.

Choosing the right threshold

This is the part where I have to be honest: I don’t have a definitive answer on the optimal threshold. It depends on your data, your embedding model, and your quality requirements.

What I can tell you from experimentation:

| Change Type | Text Diff Ratio | Should Re-embed? | Why |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typo fix (“PostgreSLQ” → “PostgreSQL”) | 0.99+ | No | Semantic meaning unchanged |

| Reformatting (whitespace, punctuation) | 0.95+ | No | Embedding models are robust to formatting |

| Single sentence rewritten | 0.85-0.95 | Maybe | Depends on the sentence’s importance |

| Paragraph added/removed | 0.70-0.85 | Yes | New information or removed context |

| Major rewrite (>30% changed) | <0.70 | Absolutely | Different document semantically |

| Metadata-only (status, category) | 1.0 (content) | No | Content columns unchanged |

My starting recommendation: set the threshold at 0.95 (i.e., re-embed when more than 5% of the text changed). Then monitor your RAG quality metrics (nDCG, retrieval precision from Part 3) and adjust. If you’re missing relevant results, lower the threshold. If you’re burning too many API credits on trivial changes, raise it.

I validated these numbers on the Wikipedia dataset in Part 2 of this post. The results cleanly confirmed the 0.95 threshold: typo fixes scored 0.998+ (SKIP), paragraph additions scored ~0.93 (EMBED), and section rewrites scored 0.51–0.63 (definitely EMBED).

The monitoring table

Whatever approach you choose, log the decisions. This is invaluable for tuning:

CREATE TABLE embedding_change_log (

log_id BIGSERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

doc_id BIGINT NOT NULL,

similarity NUMERIC(5,4), -- 0.0000 to 1.0000

decision TEXT NOT NULL, -- 'EMBED' or 'SKIP'

reason TEXT, -- 'structural_change', 'minor_change', etc.

old_content_md5 TEXT,

new_content_md5 TEXT,

details JSONB, -- optional: paragraph_similarity, char_diff, etc.

decided_at TIMESTAMPTZ NOT NULL DEFAULT now()

);

-- How many re-embeddings are we avoiding?

SELECT decision, count(*),

round(100.0 * count(*) / sum(count(*)) OVER (), 1) AS pct

FROM embedding_change_log

WHERE decided_at > now() - INTERVAL '7 days'

GROUP BY decision;

-- Result example:

-- decision | count | pct

-- ----------+-------+------

-- SKIP | 1847 | 73.2

-- EMBED | 675 | 26.8

In this example, 73% of the content changes were minor enough to skip. That’s 73% fewer embedding API calls, 73% less index churn, and a quieter, more stable RAG system.

A note on baseline: the first run

One thing that’s not obvious until you deploy this: the change detector needs existing embeddings to compare against. On the very first run, or for any document that has never been embedded, the similarity will be 0.0 (no previous embedding to compare), and the decision will always be EMBED. The SKIP optimization only kicks in on subsequent changes after a baseline exists.

This is correct behavior, but it means your initial backfill will process everything regardless of the threshold setting. Plan for it.

Full architecture recap

I won’t repeat the full Flink setup here, refer to my CDC to JDBC Sink and Oracle to PostgreSQL Migration with Flink CDC posts for the step-by-step LAB. The addition here is the significance filter sitting between the CDC source and the embedding sink.

One option I want to flag but that I haven’t fully tested at scale: embedding directly in the Flink pipeline. You could write a custom ProcessFunction that calls the embedding API and writes both the source data and the embeddings to the target in one atomic checkpoint. This eliminates the queue entirely. The concern is rate limiting and latency of embedding API calls within a streaming pipeline, if the API is slow, it creates backpressure all the way to the CDC source. For now, I’d recommend the JDBC sink + trigger + worker approach as the safer pattern, and explore inline embedding only if you have a local embedding model (like Ollama) with predictable latency.

Model Versioning: The Upgrade Problem

Everything above handles content changes. But there’s another dimension: model changes.

When you upgrade from text-embedding-3-small to text-embedding-3-large, or from v1 to v2 of any model, all your existing embeddings become incompatible. This is not optional. Different models produce different vector spaces. You cannot mix embeddings from different models in the same index — the similarity scores become meaningless.

This is why the model_version column in our schema matters. Here’s the upgrade procedure:

Step 1: Deploy new embeddings alongside old ones

-- Create a new worker (or update the config) with the new model

-- MODEL_VERSION = "v2"

-- MODEL_NAME = "text-embedding-3-large"

-- The worker will populate document_embeddings with model_version = 'v2'

-- while model_version = 'v1' embeddings remain untouched and is_current = true

Step 2: Build a separate index for the new model

-- New partial index for v2 embeddings (3072 dimensions for text-embedding-3-large)

CREATE INDEX idx_embeddings_diskann_v2 ON document_embeddings

USING diskann (embedding vector_cosine_ops)

WHERE is_current = true AND model_version = 'v2';

Step 3: Run both in parallel (shadow mode)

During shadow mode, both v1 and v2 have is_current = true, that’s intentional. Your search queries must always scope by model_version, not just is_current. Each partial index covers one version, so PostgreSQL uses the correct index when the query includes AND model_version = 'v2'.

# In your RAG query pipeline, query both and compare

results_v1 = search(query, model_version='v1')

results_v2 = search(query, model_version='v2')

# Log both, serve v1 to users, compare nDCG scores

log_comparison(query, results_v1, results_v2)

Step 4: Cut over

-- Once confident, mark v1 as not current

UPDATE document_embeddings

SET is_current = false

WHERE model_version = 'v1';

-- Drop old index

DROP INDEX idx_embeddings_diskann;

-- Optionally archive old embeddings

-- DELETE FROM document_embeddings WHERE model_version = 'v1';

Step 5: Update the worker config

Switch the worker to produce v2 embeddings for all new changes going forward.

The point is: with the versioned schema and partial indexes, model upgrades become a blue-green deployment for embeddings. No downtime, no inconsistent state, full rollback capability. This is exactly the same principle as the PostgreSQL 17→18 blue-green upgrade I wrote about, applied to vector data.

A Note on pgai Vectorizer

I want to mention pgai Vectorizer by Timescale because it solves a lot of what I’ve described above out of the box. It uses PostgreSQL triggers internally, handles automatic synchronization, supports chunking configuration, and manages the embedding lifecycle with a declarative SQL command:

SELECT ai.create_vectorizer(

'documents'::regclass,

loading => ai.loading_column('content'),

destination => ai.destination_table('document_embeddings'),

embedding => ai.embedding_openai('text-embedding-3-small', 768),

chunking => ai.chunking_recursive_character_text_splitter(500, 50)

);

After this, any INSERT/UPDATE/DELETE on documents automatically triggers re-embedding. The vectorizer worker handles batching, rate limit retries, and error recovery. It’s essentially the Level 1 pattern I described, but packaged as a production-ready tool, and since April 2025, it works with any PostgreSQL database (not just Timescale Cloud) via a Python library.

Why I still showed you the manual approach first: because in consulting, I rarely see a greenfield setup. Most projects have constraints, specific PostgreSQL versions, restricted extensions, air-gapped environments, or the need to integrate with an existing CDC pipeline. Understanding the underlying pattern lets you adapt it to your context. pgai Vectorizer is excellent if it fits your deployment, but the principles remain the same regardless of the tooling.

Monitoring Embedding Freshness

One more thing that nobody talks about: how do you know your embeddings are stale?

There are two categories of signals: infrastructure signals (is the pipeline healthy?) and quality signals (is retrieval degrading?). Most teams only monitor the first. The second is what actually matters to your users.

Infrastructure signals: pipeline health

Here are the queries I use in production to monitor the embedding pipeline itself:

-- 1. Documents with no current embeddings

SELECT d.doc_id, d.title, d.updated_at

FROM documents d

LEFT JOIN document_embeddings e

ON d.doc_id = e.doc_id AND e.is_current = true

WHERE e.embedding_id IS NULL AND d.is_active = true

ORDER BY d.updated_at DESC;

-- 2. Documents where content changed since last embedding

-- Uses LATERAL join to pick one representative row per document deterministically,

-- avoiding edge cases where chunks have mixed source_hash values (partial retries, etc.)

SELECT d.doc_id, d.title,

d.updated_at AS doc_updated,

e.embedded_at AS last_embedded,

d.updated_at - e.embedded_at AS staleness

FROM documents d

JOIN LATERAL (

SELECT embedded_at, source_hash

FROM document_embeddings

WHERE doc_id = d.doc_id

AND is_current = true

ORDER BY embedded_at DESC

LIMIT 1

) e ON true

WHERE d.is_active = true

AND d.content_hash IS DISTINCT FROM e.source_hash

ORDER BY staleness DESC;

-- 3. Queue health check

SELECT status, count(*),

avg(EXTRACT(EPOCH FROM (processed_at - claimed_at)))::int AS avg_processing_sec,

avg(EXTRACT(EPOCH FROM (claimed_at - queued_at)))::int AS avg_wait_sec

FROM embedding_queue

WHERE queued_at > now() - INTERVAL '24 hours'

GROUP BY status;

-- 4. Embedding coverage by model version

SELECT model_version,

count(DISTINCT doc_id) AS documents,

count(*) AS total_chunks,

count(*) FILTER (WHERE is_current) AS current_chunks

FROM document_embeddings

GROUP BY model_version;

Put these in a Grafana dashboard or your monitoring of choice. The staleness query (#2) is your early warning system — if documents are drifting from their embeddings, something is wrong in your pipeline.

But here’s the thing: a healthy pipeline doesn’t guarantee good retrieval. Your queue could be empty, your workers could be processing in sub-second latency, and your embeddings could still be degraded. Why? Because the pipeline only tells you that something was embedded — not that the embeddings are good.

Quality signals: when your RAG tells you embeddings are stale

This is the section I promised earlier when I said building the pipeline is one thing, but proving you’re going in the right direction is everything. This is where the work we did in the Adaptive RAG post becomes critical. The metrics we introduced there, precision@k, recall@k, nDCG@k, and confidence scores are not just evaluation tools for tuning your search weights. They are early warning signals for embedding drift.

Think about what happens when embeddings go stale:

- A document was updated with important new information, but the embedding still reflects the old content

- Similarity search retrieves the document (the old embedding is close enough), but the chunk text no longer matches the query’s intent

- The LLM generates an answer based on outdated context

- Precision drops: retrieved documents are less relevant

- nDCG drops: the ranking quality degrades because truly relevant (updated) documents are ranked lower than stale ones that happen to have closer embeddings

- Confidence drops: the gap between top results narrows, the system becomes less certain

The pattern is subtle but measurable. Here’s how to capture it.

Retrieval quality logging table

Extend the evaluation log from the Adaptive RAG post to include a timestamp dimension that allows you to track drift over time:

CREATE TABLE retrieval_quality_log (

log_id BIGSERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

query_text TEXT NOT NULL,

query_type TEXT, -- 'factual', 'conceptual', 'exploratory'

search_method TEXT NOT NULL, -- 'adaptive', 'hybrid', 'naive'

confidence NUMERIC(4,3), -- 0.000 to 1.000

precision_at_10 NUMERIC(4,3),

recall_at_10 NUMERIC(4,3),

ndcg_at_10 NUMERIC(4,3),

avg_similarity NUMERIC(4,3), -- average cosine similarity of top-10

top1_score NUMERIC(4,3), -- score of the #1 result

score_gap NUMERIC(4,3), -- gap between #1 and #2 (confidence signal)

logged_at TIMESTAMPTZ NOT NULL DEFAULT now()

);

-- Index for time-series analysis

CREATE INDEX idx_quality_log_time ON retrieval_quality_log (logged_at DESC);

The drift detection queries

Now the interesting part. These queries detect embedding staleness through retrieval quality degradation, not through pipeline metrics:

-- 5. Weekly nDCG trend — is ranking quality degrading over time?

SELECT date_trunc('week', logged_at) AS week,

round(avg(ndcg_at_10), 3) AS avg_ndcg,

round(avg(precision_at_10), 3) AS avg_precision,

round(avg(confidence), 3) AS avg_confidence,

count(*) AS queries

FROM retrieval_quality_log

WHERE logged_at > now() - INTERVAL '3 months'

GROUP BY week

ORDER BY week;

-- What you're looking for:

-- A slow, steady decline in avg_ndcg and avg_confidence over weeks

-- This is the signature of embedding drift — the pipeline is running,

-- but the embeddings are gradually falling behind the content

-- 6. Confidence distribution shift — are more queries becoming uncertain?

SELECT date_trunc('week', logged_at) AS week,

round(100.0 * count(*) FILTER (WHERE confidence >= 0.7) / count(*), 1)

AS pct_high_confidence,

round(100.0 * count(*) FILTER (WHERE confidence BETWEEN 0.5 AND 0.7) / count(*), 1)

AS pct_medium_confidence,

round(100.0 * count(*) FILTER (WHERE confidence < 0.5) / count(*), 1)

AS pct_low_confidence

FROM retrieval_quality_log

WHERE logged_at > now() - INTERVAL '3 months'

GROUP BY week

ORDER BY week;

-- If pct_low_confidence is climbing week over week, your embeddings

-- are losing alignment with the actual content

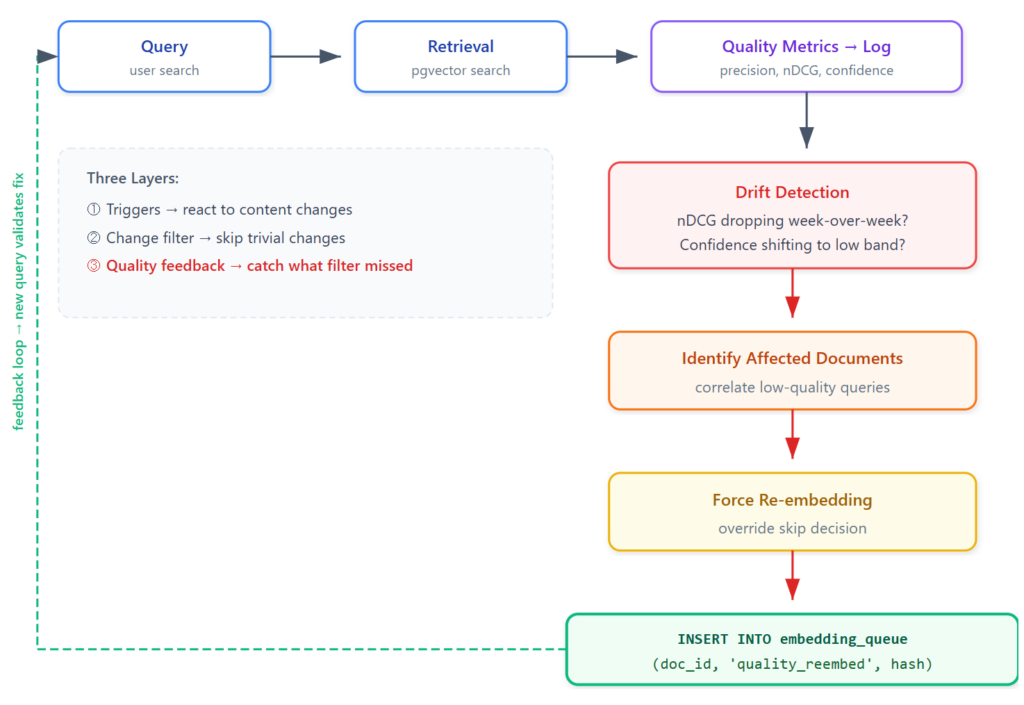

Closing the loop: from quality signal to re-embedding trigger

Here’s where this connects back to the event-driven architecture. The quality metrics don’t just sit in a dashboard, they can trigger re-embedding for documents that the pipeline’s change significance filter might have skipped.

Remember the threshold discussion from Level 3: we set a 0.95 similarity ratio as the default, meaning changes under 5% are skipped. But what if a 3% change in a critical document is causing retrieval failures?

The feedback loop:

In practice, you would implement this as a periodic job (daily or weekly) that correlates low-quality retrievals with stale documents. The correlation can be as simple as ILIKE matching query terms against document titles, or as sophisticated as tracking which document IDs were returned in low-confidence results. The key is that change_type = 'quality_reembed' is a distinct signal in your queue — it tells you the re-embedding was triggered by quality degradation, not by a content change event.

This is the complete picture: the event-driven pipeline handles the primary flow (react to data changes), the change significance filter optimizes it (skip trivial changes), and the quality monitoring loop catches what the filter missed. Three layers, each progressively more sophisticated, each compensating for the blind spots of the previous one.

As I wrote in the Adaptive RAG post: an old BI principle is to know your KPI, what it really measures but also when it fails to measure. The infrastructure metrics (queue depth, latency, skip rate) measure pipeline health. The quality metrics (precision, nDCG, confidence) measure what your users experience. You need both.

Summary

Throughout this post, we’ve covered a progression from simple to complex:

Level 1 — Triggers + Queue: Best for single-database setups. Zero external dependencies. PostgreSQL does the heavy lifting. Use LISTEN/NOTIFY for sub-second latency. This covers 80% of use cases.

Level 2 — Logical Replication: Best when source and vector databases are separate PostgreSQL instances. The source team doesn’t need to modify anything. Built-in WAL-based CDC with automatic catch-up.

Level 3 — Flink CDC + Change Significance Filtering: Best for heterogeneous sources (Oracle, MySQL) or fan-out to multiple targets. The change significance filter is the key addition — by comparing before/after images in the pipeline, you skip re-embedding for minor changes (typo fixes, metadata-only updates, formatting), which in practice eliminates 60-80% of unnecessary embedding API calls. Start with column-aware filtering, graduate to text diff ratio with a 0.95 threshold, and tune based on your RAG quality metrics.

Model Versioning: Regardless of which level you choose, version your embeddings. Track model_name, model_version, and source_hash. Use partial DiskANN indexes (pgvectorscale). Treat model upgrades like blue-green deployments.

Measurement: None of the above matters if you don’t instrument retrieval quality. The precision@k, recall@k, nDCG@k, and confidence metrics from the Adaptive RAG post aren’t a nice-to-have — they’re the only way to know whether your pipeline is actually keeping your RAG system healthy. Track them over time. Break them down by topic. Watch for drift. If you build the pipeline without the measurement layer, you’re flying blind. The evaluation framework in the pgvector_RAG_search_lab repository (lab/evaluation/) gives you a concrete starting point.

The core principle: Event-driven architecture is a precondition for production RAG — but it’s not sufficient. The moment you accept batch re-embedding as “good enough,” you’re accepting that your RAG system will silently degrade between batches. The trigger/CDC approach doesn’t just keep embeddings fresh — it gives you observability into what changed, when it was embedded, and whether the change was significant enough to matter. But the pipeline only proves that work was done. The quality metrics prove the work was effective. Log every decision. Measure the skip rate. Tune the threshold. Track nDCG weekly. This is how you operationalize RAG.

If you’ve been building RAG systems without thinking about embedding freshness, now is the time to retrofit it. And if you’re starting a new RAG project — please, design the embedding pipeline as event-driven from day one. Your future self will thank you. One of the thing that I didn’t mention as well is what should be embedded ? This is not really a technical question in the sense that it is more link to your knowledge of the data, your business, your applications, your data workflows…

What’s Next

In Part 2, I apply everything from this post to the 25,000-article Wikipedia dataset from the pgvector_RAG_search_lab repository. You’ll see:

- How to adapt the schema to an existing table (no greenfield luxury)

- Real SKIP vs EMBED decisions with actual similarity scores

- The

SKIP LOCKEDmulti-worker demo with 4 concurrent workers and zero overlap - A complete freshness monitoring report

- The quality feedback loop triggering re-embeddings automatically

A probable futur blog post would I guess, benchmarks with pgvector and diskann indexes…

![Thumbnail [60x60]](https://www.dbi-services.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/OBA_web-scaled.jpg)