Introduction

Throughout my RAG series, I’ve explored how to build retrieval-augmented generation systems with PostgreSQL and pgvector — from Naive RAG through Hybrid Search, Adaptive RAG, Agentic RAG, and Embedding Versioning (not yet released) . The focus has always been on retrieval quality: precision, recall, nDCG, confidence.

But I want to take a step back.

In conversations with colleagues, clients, and fellow PostgreSQL enthusiasts — most recently at the PG Day at CERN — I keep running into the same fundamental question: which paradigm should we use to connect LLMs to our data? Not “which is best for retrieval quality” but “which can we actually deploy in a regulated environment where data governance isn’t optional?”

Because in banking, healthcare, or any FINMA-regulated context, the question is never just “does it work?” The question is: can you prove it works safely, explain how it works, and guarantee it respects access controls?

Today, three paradigms dominate how LLMs interact with structured and unstructured data:

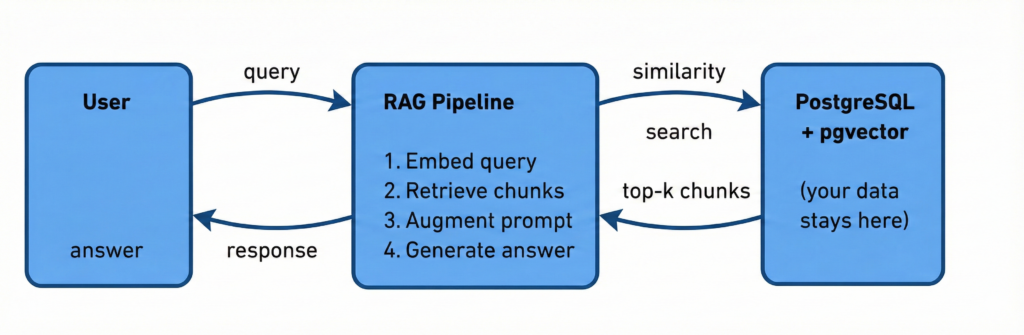

- RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation): the LLM receives pre-retrieved context, never touches the database directly

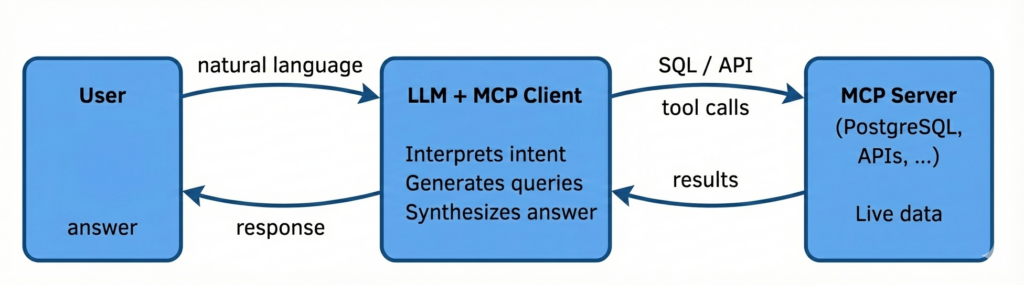

- MCP (Model Context Protocol): the LLM generates and executes queries against live data sources through standardized tool interfaces

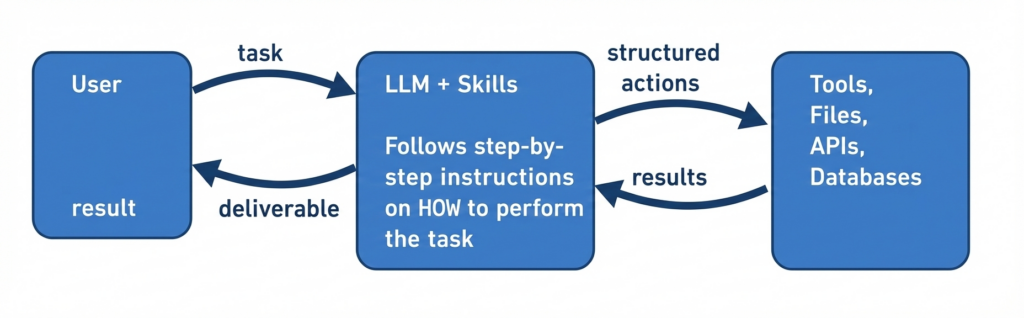

- Skills: the LLM follows procedural instructions that define not just what to answer, but how to perform tasks step by step

Each one draws the trust boundary in a fundamentally different place. And that changes everything for governance.

But let me be clear upfront: these three paradigms are complementary, not competing. There is overlap between them, and in some cases one can partially do what another does. But they each have distinct strengths, and the real architectural question is not “which one should I pick?” but “where in my system does each one belong?” A well-designed LLM-powered application might use RAG for knowledge retrieval, MCP for analytical queries, and Skills for procedural workflows — all within the same product, each governed appropriately for its trust model. The mistake I see teams make is treating this as an either/or decision when it’s fundamentally a composition problem.

It’s also worth noting that the boundaries between these paradigms are already blurring. Some MCP servers now leverage RAG components built-in — vector search as a tool the LLM can call, rather than a separate pipeline. And over the past months, MCP itself has become increasingly abstracted: higher-level orchestration layers sit on top, hiding the protocol details from both the LLM and the developer. The consequence is that the frontiers between RAG, MCP, and Skills are becoming harder to draw cleanly.

This mirrors something I’ve observed more broadly in IT. Before AI-driven data workflows, roles had clear separations and were (too) easily siloed: infrastructure admins managed servers, developers wrote application code, DBAs owned the database layer. Each team had its perimeter, its tools, its responsibilities. With AI data workflows, the overlap and shared responsibilities are growing — the DBA needs to understand how the LLM consumes data, the developer needs to understand database-level access controls, the security team needs to understand embedding pipelines and prompt behavior. The silos don’t hold anymore. And I think this is actually one of the positive consequences of this shift: at least in IT, people will have to talk more and break silos. The governance challenges I’ll describe in this post are not solvable by any single team in isolation.

A Quick Overview: What Each Paradigm Does

Before diving into governance, let’s make sure we’re on the same page about what each paradigm actually does. I’ll keep this brief because the nuances matter more than the definitions.

RAG — The LLM Reads What You Give It

The LLM never sees your database. It sees chunks of text that a retrieval layer selected based on vector similarity. The database is behind a wall — the RAG pipeline decides what crosses it.

This is the paradigm I’ve spent the most time on in my series, and there’s a reason: from a DBA’s perspective, it’s the most controllable. Row-Level Security, data masking, column filtering, TDE — all the tools we’ve spent years mastering apply directly, because the retrieval layer queries the database on behalf of the user, and the database enforces its own rules.

MCP — The LLM Talks to Your Database

With MCP (Anthropic’s Model Context Protocol), the LLM doesn’t receive pre-filtered chunks. It receives tools — standardized interfaces to data sources, APIs, and services. The LLM decides which tool to call, formulates the query (often SQL), and interprets the results.

This is powerful. The LLM can explore data, join across tables, aggregate, filter — things that are impossible in a RAG pipeline where the retrieval is limited to vector similarity over pre-chunked text.

But the trust boundary has moved. The LLM is now an active agent inside your data perimeter, not a passive consumer of pre-filtered context.

Skills — The LLM Follows Your Procedures

Skills go beyond querying data. A Skill is a set of instructions that tells the LLM not just what to answer, but how to perform a task — step by step, with specific tools, in a specific order, following specific constraints. Think of it as encoding a procedure, a runbook, or an expertise template that the LLM executes.

For example: a Skill might instruct the LLM to read a client’s portfolio from the database, apply risk weighting rules from a compliance document, generate a report in a specific format, and flag any positions that exceed regulatory thresholds — all as a single orchestrated workflow.

The trust boundary hasn’t just moved — it has expanded. The LLM is no longer just reading data or generating queries. It’s executing multi-step procedures that combine data access, computation, and output generation.

The Trust Boundary Problem

Here’s the framework I use when advising clients on these paradigms. It comes down to one question: where does the security perimeter sit, and who crosses it?

| Feature | RAG | MCP | Skills |

| Trust boundary | Pipeline acts as gatekeeper | LLM acts as query agent | LLM acts as procedure executor with tool access |

| LLM sees | Pre-filtered chunks only | Raw query results from live DB | Raw data + intermediate computation results |

| DBA controls | ✅ Full (RLS, masking, filtering at retrieval time) | ⚠️ Partial (connection-level, but LLM can infer beyond single query) | ❌ Minimal (depends on Skill design and LLM behavioral compliance) |

Let me unpack each one.

RAG: The DBA’s Comfort Zone

I’ll be direct: RAG is where I’m most comfortable as a DBA, and there are solid reasons for that.

Why governance is straightforward

In a RAG architecture, the retrieval layer is a regular database client. It connects with a specific role, it runs queries (vector similarity search), and it returns results. Everything the DBA has built over the past decades applies:

Row-Level Security (RLS): You can enforce per-user access policies at the PostgreSQL level. If user A shouldn’t see documents classified as “confidential-level-3”, the RLS policy filters them out before the embedding search even returns results. The LLM never sees them — not in the chunks, not in the context, not in the answer.

-- Example: RLS on the document_embeddings table

CREATE POLICY embedding_access ON document_embeddings

FOR SELECT

USING (

doc_id IN (

SELECT doc_id FROM documents

WHERE classification_level <= current_setting('app.user_clearance')::int

)

);

Data masking: If certain fields need to be masked (client names, account numbers), you apply masking rules at the view or column level. The chunks the LLM receives already have masked data. There’s no risk of the LLM “accidentally” revealing something it shouldn’t — it never had it.

Audit logging: Every query to the vector store is a standard SQL query. pgaudit, log_statement, your existing monitoring — it all works. You can trace exactly which chunks were retrieved for which query at which time.

TDE (Transparent Data Encryption): Embeddings at rest are encrypted like any other column. pgcrypto or filesystem-level encryption applies without modification.

The measurement advantage

This is the point I made in my Adaptive RAG post: RAG has a well-defined quality measurement framework.

You build golden question/answer pairs with domain experts. You run the retrieval pipeline against these pairs. You measure precision@k, recall@k, nDCG@k. You track these over time (as I described in the embedding versioning post).

The key property is that the output space is bounded: given a query, the system returns a ranked list of chunks. You can evaluate whether the right chunks were returned, in the right order, with the right confidence. This is a well-studied problem in information retrieval — decades of academic work support it.

The limitations

RAG is not universally applicable, and I don’t want to oversell it:

- It can’t do aggregation: “What’s the total exposure across all clients in sector X?” requires a SQL query, not a similarity search over chunks.

- It can’t join across data sources: if the answer requires combining data from multiple tables or systems, the pre-chunked approach breaks down.

- It’s bound by the chunking strategy: if the relevant information spans multiple chunks, or if the chunking split a critical paragraph, retrieval quality suffers regardless of how good your embeddings are.

- It requires upfront indexing: every document must be chunked and embedded before it can be retrieved. The event-driven pipelines I described in the embedding versioning post address the freshness problem, but the fundamental constraint remains.

These limitations are exactly what push teams toward MCP.

MCP: When the LLM Writes the Queries

MCP is compelling because it removes the constraints I just listed. The LLM can query live data, aggregate, join, filter — anything SQL can express. For analytical workloads, it’s transformative.

But the governance implications are profound.

The identity problem: who is the user?

In a traditional application, the database sees a connection from a known application user with a defined role. RLS policies evaluate current_user or current_setting('app.user_id'), and access is scoped accordingly.

With MCP, the LLM is the intermediary. The MCP server connects to PostgreSQL, but who is the user? Is it:

- The human who asked the question?

- The LLM instance processing the request?

- The MCP server’s service account?

In most current MCP implementations, it’s the service account. The MCP server connects with a single set of credentials, and the LLM’s queries execute with that role’s permissions. This creates a fundamental problem in regulated environments: the database cannot distinguish between queries on behalf of different users with different access levels.

You can work around this with application-level filtering — the MCP server injects WHERE clauses based on the requesting user’s profile. But this moves access control from the database (where it’s declarative, auditable, and enforced by the engine) to the application layer (where it depends on correct implementation, and where the LLM might find creative ways around it).

This is where I have a hard time enforcing data privacy rules outside of the RAG paradigm. As a DBA, tools like RLS, TDE, data masking, and filtering are well-known and battle-tested. In an MCP paradigm, these tools still exist at the database level, but the trust that they’ll be invoked correctly now depends on the MCP server’s implementation and the LLM’s behavioral compliance.

The inference problem

This is the subtler issue and, in my opinion, the more dangerous one for FINMA-regulated environments.

Even if you perfectly control what data the LLM can query, the LLM can infer information by combining results from multiple queries. Consider:

- Query 1: “How many clients are in sector Energy?” → 3

- Query 2: “What’s the total exposure in sector Energy?” → CHF 450M

- Query 3: “What’s the largest single position across all sectors?” → CHF 200M

Individually, each query might be within the user’s access rights. But combined, the LLM can infer: “One client in the Energy sector represents nearly half the total exposure — approximately CHF 200M.” This might be information the user is not authorized to derive.

This is not a new problem — it’s the classic inference attack from database security literature. But LLMs make it dramatically easier because:

- They’re excellent at combining information from multiple queries

- They do it naturally, without being explicitly instructed to

- The user might not even realize they received derived information they shouldn’t have

In a RAG architecture, the inference surface is much smaller because the LLM only sees pre-selected chunks, not raw query results it can freely combine.

The auditability challenge

In FINMA’s operational risk framework (and Basel III/IV more broadly), financial institutions must maintain comprehensive audit trails for data access. This means you need to answer: who accessed what data, when, and for what purpose?

With MCP:

- The “who” is partially obscured (service account vs. actual user)

- The “what” is a generated SQL query that might be complex and non-obvious

- The “for what purpose” is the natural language question, which may not clearly map to the data accessed

You can log everything — the natural language input, the generated SQL, the results, the final answer. But the audit trail is now multi-layered and interpretive: a compliance officer reviewing the logs needs to understand not just that a query ran, but why the LLM chose that particular query, and whether the answer faithfully represents the data without unauthorized inference.

Compare this to RAG, where the audit trail is: “User asked X. The system retrieved chunks Y1, Y2, Y3 from documents the user has access to. The LLM generated answer Z based on those chunks.” Simpler. More linear. Easier to review.

Where MCP shines despite the challenges

I don’t want to paint MCP as undeployable. It solves real problems:

- Analytical queries: “Show me the monthly trend of client onboarding over the past year” — this requires aggregation that RAG simply cannot do

- Exploratory data access: when users don’t know exactly what they’re looking for, the ability to query flexibly is invaluable

- Multi-source integration: MCP servers can connect to multiple backends (PostgreSQL, APIs, file systems) through a single standardized protocol

- Reduced indexing overhead: no need to chunk, embed, and maintain vector indexes — the data is queried live

The measurement story is also more tractable than Skills (see below). Academic work on text-to-SQL evaluation provides established benchmarks. Projects like WikiSQL and BIRD-SQL offer golden datasets of natural language questions paired with correct SQL queries and expected results.

However — and this is a crucial point I raised during discussion with colleagues — these academic benchmarks don’t transfer to your specific domain. WikiSQL doesn’t know your banking schema. BIRD-SQL doesn’t understand your compliance rules. You still need to build your own evaluation dataset with domain experts, golden queries, and expected results specific to your data model.

The good news: the methodology transfers. You know what to measure (query correctness, result accuracy, execution safety). You know how to structure the evaluation (golden pairs). The work is in building the domain-specific test suite, not in inventing the evaluation framework.

Skills: When the LLM Executes Procedures

Skills represent the most powerful — and the most challenging — paradigm from a governance perspective.

In a Skill, the LLM is not just retrieving information or generating queries. It’s following a procedural set of instructions that might involve: reading data, applying business logic, making decisions based on intermediate results, generating outputs in specific formats, and potentially writing data back.

The instruction adherence problem

With RAG, you measure retrieval quality. With MCP, you measure query correctness. With Skills, you need to measure something much harder: did the LLM follow the procedure correctly?

Two responses can both be “compliant” with a Skill’s instructions and yet differ significantly in quality. Consider a Skill that instructs the LLM to:

- Read a client’s transaction history from the database

- Apply anti-money-laundering (AML) screening rules

- Flag suspicious patterns according to FINMA guidelines

- Generate a structured report

Response A might flag 5 transactions as suspicious, with clear reasoning linked to specific FINMA rules. Response B might flag 3 of the same 5, miss 2 edge cases, but also flag 1 false positive — with equally valid-sounding reasoning. Both followed the Skill’s instructions. Both produced structured reports. But one is meaningfully better than the other.

How do you measure this? This is the question that keeps me up at night, and I don’t have a clean answer.

For RAG, we have precision, recall, nDCG — well-defined metrics with decades of research behind them. For MCP/text-to-SQL, we have execution accuracy, result set matching, and query equivalence. For Skills, we need to evaluate:

- Instruction adherence: did the LLM follow each step in order?

- Completeness: were all required steps executed?

- Correctness of intermediate decisions: at each decision point, did the LLM make the right call?

- Output quality: does the final deliverable meet the specification?

- Safety: did the LLM stay within the boundaries of the Skill, or did it improvise?

This is by far more subjective and creates more edge cases. You can build evaluation frameworks for each of these dimensions, but the composite “is this response good?” judgment requires human review at a level that doesn’t scale easily.

The behavioral safety gap

In regulated environments, the process matters as much as the result. In banking, it’s not enough to produce the correct AML report — you must produce it through the correct procedure, applying the correct rules, in the correct order, with the correct audit trail.

Skills encode this process. But the LLM is a probabilistic system. It will sometimes:

- Reorder steps when it “thinks” a different order is equivalent (it might not be, regulatorily)

- Skip a step it deems unnecessary (it might be required for compliance)

- Interpolate between the Skill’s instructions and its general training (introducing reasoning that wasn’t prescribed)

- Handle edge cases creatively (which might mean non-compliantly)

In a FINMA audit, “the AI decided to skip step 3 because it seemed redundant” is not an acceptable explanation. The procedure exists for a reason. Compliance is about following the prescribed process, not just arriving at a plausible result.

The data access surface

Skills often need broad data access to perform their multi-step procedures. An AML screening Skill might need access to transaction history, client profiles, country risk ratings, and regulatory threshold configurations. This is a wide data surface — wider than most RAG retrieval patterns and potentially wider than individual MCP queries.

The challenge is that this access is implicit in the Skill design, not explicit in a per-query access control check. When the Skill says “read the client’s transaction history,” the underlying MCP call or database query is executed with whatever permissions the Skill’s execution context has. There’s no natural point where a per-user RLS check happens unless you’ve specifically engineered it into the Skill’s execution layer.

The Governance Matrix

Let me bring this together in a framework that I’ve found useful when discussing these paradigms with CISOs and compliance teams:

| Governance Dimension | RAG | MCP | Skills |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data access control | ✅ Database-native (RLS, views, masking) — data is filtered before the LLM sees it | ⚠️ Depends on MCP server implementation; LLM sees raw query results | ❌ Broad access often required; implicit in Skill design |

| Inference protection | ✅ Limited surface — LLM sees only pre-selected chunks | ⚠️ LLM can combine results from multiple queries to derive unauthorized information | ❌ Multi-step procedures inherently combine information |

| Audit trail clarity | ✅ Linear: query → chunks → answer. Easy to review | ⚠️ Multi-step: question → SQL(s) → results → answer. Requires interpretation | ❌ Complex: task → steps → intermediate results → decisions → output. Hard to audit |

| Identity propagation | ✅ Retrieval runs as the user (or user-scoped service) | ⚠️ MCP server connects with service account; user identity must be passed through | ⚠️ Execution context may not map to individual user identity |

| Relevance measurement | ✅ Mature: precision, recall, nDCG on golden datasets | ⚠️ Text-to-SQL benchmarks exist but must be domain-adapted | ❌ Instruction adherence is subjective; no standard metrics |

| Behavioral predictability | ✅ Output bounded by retrieved context | ⚠️ LLM chooses which queries to run; output depends on query strategy | ❌ LLM executes procedures; may reorder, skip, or improvise steps |

| Regulatory explainability | ✅ “The system retrieved these documents and generated this answer” | ⚠️ “The system ran these queries and synthesized this answer” | ❌ “The system followed this procedure, making these intermediate decisions” |

| Data residency / TDE | ✅ Standard PostgreSQL encryption; chunks are just rows | ✅ Standard — queries execute within the DB perimeter | ⚠️ Intermediate results may exist outside the DB during processing |

| Anonymization-utility balance | ✅ Transformation at embedding time; LLM only sees pre-abstracted chunks | ⚠️ Transformation at query time; every query path must return abstracted data | ❌ Transformation needed at every procedure step; hard to guarantee consistency |

The trend is clear: as you move from RAG to MCP to Skills, the governance burden shifts from the database to the application layer, and the DBA’s ability to enforce controls diminishes.

This doesn’t mean MCP and Skills are unusable in regulated environments. It means the governance responsibility shifts, and different teams need to own different pieces.

The Real Challenge: Anonymization Is Not Enough

The governance matrix above might give the impression that the hard problem is access control — deciding whether the LLM sees the data. In practice, at least in the enterprise environments where I consult, the harder problem is what happens to the data before the LLM sees it.

Everyone agrees on the baseline: strip PII before sending anything to an external LLM. Replace client names with tokens, mask account numbers, redact personal identifiers. This is table stakes, and there are mature tools for it — both at the PostgreSQL level (dynamic masking, views) and at the application layer (regex-based scrubbing, NER-based entity detection).

But here’s what nobody warns you about: if you anonymize too aggressively, the LLM can’t do its job. And if you don’t anonymize enough, you’ve just sent regulated data to a third-party API.

The balance is not a binary “mask or don’t mask.” It’s a spectrum of semantic-preserving transformation — and finding the right point on that spectrum is, in my experience, the most under-discussed practical challenge of deploying LLMs in regulated environments.

The anonymization-utility trade-off

Let me illustrate with a concrete example from a banking context. Suppose a relationship manager asks the RAG system: “What are the key risk factors for this client’s portfolio?”

The original chunk from the knowledge base might contain:

Client: Jean-Pierre Müller (ID: CH-98234)

Portfolio value: CHF 4.2M

Concentrated position: 47% in Nestlé S.A. (NESN.SW)

Recent transactions: Sold CHF 200K of Roche Holding AG on 2025-11-15

KYC renewal due: 2026-03-01

Risk rating: Medium-High (upgraded from Medium on 2025-09-20)

Now let’s look at what happens at different levels of anonymization:

Level 1 — PII-only masking (replace identifiers, keep everything else):

Client: [CLIENT_A] (ID: [REDACTED])

Portfolio value: CHF 4.2M

Concentrated position: 47% in Nestlé S.A. (NESN.SW)

Recent transactions: Sold CHF 200K of Roche Holding AG on 2025-11-15

KYC renewal due: 2026-03-01

Risk rating: Medium-High (upgraded from Medium on 2025-09-20)

The LLM can still reason perfectly about the portfolio risk. It sees the concentration in a specific stock, the transaction history, the risk upgrade. This is semantically rich — the answer will be excellent.

But the problem: Nestlé + Roche + CHF 4.2M + specific dates might be enough to re-identify the client through correlation. A determined actor with access to client lists could narrow this down to a handful of people, potentially one. The PII is gone, but the data fingerprint remains.

Level 2 — Aggressive anonymization (mask everything that could identify):

Client: [CLIENT_A] (ID: [REDACTED])

Portfolio value: [AMOUNT]

Concentrated position: [PERCENTAGE] in [COMPANY_A]

Recent transactions: Sold [AMOUNT] of [COMPANY_B] on [DATE]

KYC renewal due: [DATE]

Risk rating: [RATING] (upgraded from [PREVIOUS_RATING] on [DATE])

Now the data is safe from re-identification. But the LLM is blind. It can’t tell you that a 47% concentration in a single stock is a risk factor, because it doesn’t know it’s 47%. It can’t assess whether the recent sale was material, because it doesn’t know the amount relative to the portfolio. It can’t flag the KYC timeline. The answer will be generic boilerplate about portfolio risk — useless to the relationship manager.

Level 3 — Semantic-preserving abstraction (this is where the real work happens):

Client: [CLIENT_A] (ID: [REDACTED])

Portfolio value: CHF 4-5M range

Concentrated position: >40% in a single Swiss large-cap equity

Recent transactions: Significant sale in Swiss pharma sector, Q4 2025

KYC renewal due: Q1 2026

Risk rating: Medium-High (recently upgraded)

Now we’ve achieved something interesting. The data is:

- Not re-identifiable: ranges, sectors, and quarters instead of exact values, company names, and dates

- Semantically sufficient: the LLM can still reason that >40% in a single stock is a concentration risk, that a significant sale in pharma might be rebalancing, that a recent risk upgrade plus upcoming KYC renewal warrants attention

- Contextually accurate: the abstraction preserves the relationships between data points (concentration → risk rating → KYC timeline)

This is the sweet spot — but getting there requires deliberate design, not just running a PII scanner.

Building the abstraction layer: data mapping in PostgreSQL

In practice, I implement this as a transformation layer in PostgreSQL — views or functions that produce the “LLM-safe” version of the data, with the abstraction rules encoded declaratively.

-- Abstraction mapping for amounts

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION anonymize_amount(amount NUMERIC, currency TEXT DEFAULT 'CHF')

RETURNS TEXT AS $$

BEGIN

-- Preserve magnitude and currency, remove precision

RETURN CASE

WHEN amount < 100000 THEN currency || ' <100K'

WHEN amount < 500000 THEN currency || ' 100K-500K range'

WHEN amount < 1000000 THEN currency || ' 500K-1M range'

WHEN amount < 5000000 THEN currency || ' 1-5M range'

WHEN amount < 10000000 THEN currency || ' 5-10M range'

WHEN amount < 50000000 THEN currency || ' 10-50M range'

ELSE currency || ' 50M+'

END;

END;

$$ LANGUAGE plpgsql IMMUTABLE;

-- Abstraction mapping for dates (reduce to quarter)

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION anonymize_date(d DATE)

RETURNS TEXT AS $$

BEGIN

RETURN 'Q' || EXTRACT(QUARTER FROM d)::TEXT || ' ' || EXTRACT(YEAR FROM d)::TEXT;

END;

$$ LANGUAGE plpgsql IMMUTABLE;

-- Abstraction mapping for percentages (bucketize)

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION anonymize_percentage(pct NUMERIC)

RETURNS TEXT AS $$

BEGIN

RETURN CASE

WHEN pct < 10 THEN '<10%'

WHEN pct < 25 THEN '10-25%'

WHEN pct < 40 THEN '25-40%'

WHEN pct < 60 THEN '>40%' -- "concentrated"

WHEN pct < 80 THEN '>60%' -- "highly concentrated"

ELSE '>80%' -- "dominant position"

END;

END;

$$ LANGUAGE plpgsql IMMUTABLE;

-- Sector mapping: company → sector (prevents re-identification via company name)

CREATE TABLE company_sector_map (

company_name TEXT PRIMARY KEY,

sector TEXT NOT NULL, -- 'Swiss pharma', 'European tech', etc.

market_cap_tier TEXT NOT NULL -- 'large-cap', 'mid-cap', 'small-cap'

);

-- The LLM-safe view: this is what gets chunked and embedded (for RAG)

-- or what the MCP server exposes (for MCP)

CREATE OR REPLACE VIEW v_portfolio_llm_safe AS

SELECT

p.client_id, -- internal ref only

anonymize_amount(p.portfolio_value) AS portfolio_size,

anonymize_percentage(p.concentration_pct)

|| ' in a single '

|| csm.market_cap_tier

|| ' ' || csm.sector AS concentration_description,

anonymize_amount(t.amount) || ' in ' || csm_t.sector

|| ', ' || anonymize_date(t.trade_date) AS recent_activity,

anonymize_date(p.kyc_renewal_date) AS kyc_timeline,

p.risk_rating,

CASE WHEN p.risk_rating_changed_at > now() - INTERVAL '6 months'

THEN 'recently upgraded' ELSE 'stable'

END AS risk_trend

FROM portfolios p

LEFT JOIN company_sector_map csm ON p.top_holding = csm.company_name

LEFT JOIN LATERAL (

SELECT amount, trade_date, company_name

FROM transactions

WHERE client_id = p.client_id

ORDER BY trade_date DESC LIMIT 1

) t ON true

LEFT JOIN company_sector_map csm_t ON t.company_name = csm_t.company_name;

The key design principles:

Bucketize, don’t mask. Instead of replacing CHF 4.2M with [REDACTED], replace it with CHF 1-5M range. The LLM loses precision but retains the magnitude — and magnitude is what drives most reasoning. The bucket boundaries should be defined with the business: what granularity does the LLM need to produce useful answers?

Abstract to sector, not to nothing. Instead of removing Nestlé S.A., replace it with Swiss large-cap equity. The LLM can still reason about sector concentration, geographic exposure, and market cap risk. A company_sector_map table (maintained by the business or compliance team) drives this consistently.

Preserve relationships, anonymize individuals. The temporal relationship between risk rating upgrade, KYC renewal, and recent trading activity is preserved — recently upgraded + Q1 2026 KYC + Q4 2025 sale. The LLM can reason about the pattern without knowing who, exactly how much, or which stock.

Encode the rules declaratively. The abstraction logic lives in PostgreSQL views and functions, not in application code. This means it’s auditable (you can review the view definition), testable (run the view and inspect the output), and consistent (every query path through this view applies the same rules).

The mapping problem: when context requires real entities

Here’s where it gets genuinely hard. Some questions require the LLM to know real entity names to be useful.

“Should the client reduce their Nestlé position given the recent earnings miss?”

If you’ve abstracted Nestlé to “Swiss large-cap FMCG,” the LLM can’t connect it to actual earnings data. It can give generic advice about concentration risk, but it can’t reason about Nestlé-specific fundamentals — which is what the relationship manager actually needs.

There are two approaches I’ve seen work in practice:

Approach A — Split context, split model calls. Use the anonymized context for client-specific reasoning (portfolio risk, concentration, suitability) and a separate, non-anonymized call for market/public data reasoning (Nestlé earnings, sector outlook). The LLM never sees both the client identity and the company name in the same context. The application layer merges the two responses.

Call 1 (anonymized): "Client has >40% concentration in a single

Swiss large-cap FMCG stock. Risk rating recently

upgraded. Assess concentration risk."

Call 2 (public data): "Analyze recent Nestlé S.A. earnings and

outlook for institutional holders."

Application layer: Merge both responses for the RM.

This is architecturally clean but operationally complex. You need a reliable merging layer, and the LLM can’t reason holistically across both contexts.

Approach B — Reversible pseudonymization with a mapping table. Replace real entities with consistent pseudonyms that the LLM treats as real entities. The mapping is stored in PostgreSQL, never sent to the LLM, and used by the application layer to re-hydrate the response before displaying it to the user.

-- Pseudonym mapping (never exposed to the LLM)

CREATE TABLE entity_pseudonyms (

real_name TEXT PRIMARY KEY,

pseudonym TEXT UNIQUE NOT NULL,

entity_type TEXT NOT NULL -- 'company', 'person', 'fund'

);

-- Example entries:

-- ('Nestlé S.A.', 'Alpine Corp', 'company')

-- ('Roche Holding AG', 'Glacier Pharma', 'company')

-- ('Jean-Pierre Müller', 'Client Alpha', 'person')

The LLM sees: “Client Alpha has a 47% position in Alpine Corp and recently sold Glacier Pharma stock.” It can reason about concentration, sector correlation, and transaction patterns using these pseudonyms as if they were real entities. The application layer maps the pseudonyms back to real names before showing the response to the user.

The advantage: the LLM gets rich, entity-level context. It can reason about “Alpine Corp” as a coherent entity across multiple chunks and queries.

The risk: pseudonym consistency must be airtight. If “Alpine Corp” appears as “Nestlé” in one chunk due to a mapping error, you’ve leaked. The mapping table must be maintained carefully, and the transformation must happen at a single controlled layer — ideally the PostgreSQL view, not scattered across application code.

How this differs across paradigms

The anonymization-utility balance plays out differently depending on the paradigm:

RAG: You control the transformation at embedding time. The chunks stored in pgvector can already be the anonymized/abstracted version. The LLM never has the opportunity to see raw data — it’s been transformed before it was even indexed. This is the safest model, and it’s where the PostgreSQL view approach works best: embed from v_portfolio_llm_safe, not from the raw tables.

MCP: The transformation must happen at query time, in the MCP server. This is harder because the LLM generates arbitrary SQL, and you need to ensure that every possible query path returns abstracted data. You can force the MCP server to query through the anonymized views rather than the base tables, but you need to be rigorous about not exposing the raw tables at all. One misconfigured permission and the LLM can SELECT * FROM portfolios directly.

Skills: The transformation must happen at every step of the procedure where data flows through the LLM’s context. A multi-step Skill might read raw data in step 1, transform it in step 2, and reason about it in step 3 — but if the Skill’s instructions aren’t precise about when and how to transform, the LLM might shortcut the process and pass raw data into its reasoning context.

The pattern is consistent with the governance matrix: as you move from RAG to MCP to Skills, maintaining the anonymization-utility balance gets progressively harder because you have less control over when and how the LLM encounters the data.

The measurement gap

Finally, there’s a quality measurement dimension to this that I haven’t seen well-addressed anywhere.

When you anonymize or abstract data before sending it to the LLM, you need to verify that the transformation didn’t destroy the LLM’s ability to answer correctly. This means your golden question/answer evaluation pairs (from the Adaptive RAG post) need to be run on the abstracted data, not the raw data.

If your nDCG score drops from 0.85 on raw data to 0.62 on abstracted data, your bucketization is too aggressive — the LLM is losing too much context. If it stays at 0.83, the abstraction is working. You need to measure this explicitly during development, and re-measure whenever you change the abstraction rules.

This creates a feedback loop between the security team (who wants maximum anonymization) and the business team (who wants maximum answer quality). The DBA sits in the middle, tuning the PostgreSQL views and measuring the impact. In my experience, this negotiation — finding the right bucket boundaries, the right sector mappings, the right level of temporal abstraction — takes more time than building the RAG pipeline itself. But it’s the work that makes the difference between a system that compliance signs off on and one that stays in the sandbox.

What FINMA Expects (and Where Each Paradigm Stands)

Without going into a full regulatory analysis, FINMA’s Circular 2023/1 on operational risks and resilience and the broader EBA guidelines on ICT and security risk management establish expectations that directly affect paradigm choice:

Traceability and auditability: every data access must be traceable to a specific user, purpose, and time. RAG satisfies this naturally through database audit logs. MCP requires careful logging at the server layer. Skills require comprehensive step-by-step execution logging.

Data classification enforcement: sensitive data must be protected according to its classification level. RAG enforces this at retrieval time via RLS and masking. MCP and Skills require the enforcement to happen at the tool/execution layer, with no guarantee that the LLM won’t combine or infer beyond what’s permitted.

Outsourcing and third-party risk: if the LLM is a cloud service (OpenAI, Anthropic API), the data sent to it matters. RAG sends chunks — you control exactly what leaves your perimeter. MCP sends query results — potentially broader. Skills might send intermediate computation results, client data, or procedure outputs.

Model risk management: FINMA expects institutions to understand and manage model risk. For RAG, the “model” is the embedding model + the retrieval logic — both well-defined and testable. For MCP, the model risk includes the LLM’s query generation behavior. For Skills, the model risk encompasses the LLM’s procedural execution behavior — much harder to bound.

The Irony: We Need Databases Again

I want to close with an observation that keeps coming back to me.

As LLM-powered applications grow more complex — longer conversations, more context, more tools, more steps — we’re running into a fundamental problem: how do you manage context effectively across long-running interactions?

Today’s LLMs have fixed context windows. When the conversation exceeds that window, information is lost. The current solutions? Summarization (lossy), truncation (lossy), or… indexing the context into retrievable storage and fetching relevant pieces when needed.

Sound familiar? That’s essentially what databases have been doing since the 1960s. There’s a recent paper on Recursive Language Models that literally recreates context indexing into files to improve accuracy and avoid losing details in long-running conversations. It’s the application-database paradigm, but at the ISAM level.

The irony is not lost on me. We spent decades building sophisticated data management systems — indexing, caching, query optimization, transaction management, access control. Now the AI community is rediscovering these patterns from first principles, often without the benefit of the lessons we’ve already learned.

As the AI ecosystem matures, I believe we’ll see the database layer become more central, not less. Whether it’s pgvector for RAG, PostgreSQL as an MCP server, or a context store for long-running agent conversations — the principles of data management don’t change just because the client is a language model instead of a human.

And that’s good news for those of us who’ve spent our careers in databases. The skills transfer. The patterns transfer. RLS still works. Audit logging still matters. ACID still matters. The challenge is adapting our expertise to new trust boundaries and new failure modes.

Summary

The choice between RAG, MCP, and Skills is not primarily a technical decision. It’s a governance decision.

RAG keeps the LLM outside the data perimeter. MCP lets the LLM inside, as a query agent. Skills give the LLM the keys to execute procedures. Each step outward increases capability but also increases the surface area for data leakage, inference attacks, and compliance failures.

There’s another dimension to this progression that deserves explicit attention: as you move from RAG to MCP to Skills, you are also shifting trust from your own architecture to the LLM platform provider. With RAG, the LLM is a stateless text generator — your retrieval pipeline, your database, your access controls do the heavy lifting. With MCP and Skills, you are increasingly relying on the LLM’s behavioral compliance, its tool-use reliability, and the platform’s guarantees around data handling, logging, and isolation. In practice, this means trusting Anthropic, OpenAI, or whichever provider powers your inference layer to uphold the security properties your regulator demands.

To their credit, these providers are investing heavily in enterprise readiness. Anthropic and OpenAI both now offer features specifically designed for regulated environments — data residency controls, zero data retention options, SOC 2 compliance, audit logging, and increasingly granular access management. The MCP specification itself was donated to the Linux Foundation’s Agentic AI Foundation in December 2025, signaling a move toward vendor-neutral governance of the protocol layer. These are meaningful steps. But they don’t change the fundamental architectural reality: every capability you delegate to the LLM platform is a capability you no longer enforce within your own perimeter. For a CISO in a FINMA-regulated institution, “the provider is SOC 2 compliant” is a necessary condition, not a sufficient one.

For regulated environments — banking, healthcare, critical infrastructure — this progression matters. The question is not “which paradigm is most powerful?” but “which paradigm can I govern, audit, and explain to my regulator?”

As a DBA, my bias is clear: keep as much as possible within the database’s governance perimeter. PostgreSQL’s security model has been battle-tested for decades. The LLM is a powerful new client — but it’s still a client, and the database’s rules should still apply. Data pipelines should allow you to set up within the architecture a vertical defensibility and decouple your governance and business logic from the LLM.

The industry will figure out governance for MCP and Skills. The academic work on text-to-SQL evaluation is advancing. The tooling for behavioral evaluation of AI agents is improving. Enterprise features from LLM providers will continue to mature. But today, in February 2026, if a CISO asks me “can I deploy this safely?” — for RAG, I can say yes with confidence. For MCP, I can say yes with caveats. For Skills, I say: let’s build the evaluation framework first.

![Thumbnail [60x60]](https://www.dbi-services.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/OBA_web-scaled.jpg)